|

|

- Search

| Ann Child Neurol > Epub ahead of print |

Abstract

Purpose

Methods

Results

Conflicts of interest

Soonhak Kwon is an editor-in-chief of the journal, but he was not involved in the peer reviewer selection, evaluation, or decision process of this article. No other potential conflicts of interest relevant to this article were reported.

Notes

Author contribution

Conceptualization: SK. Data curation: SL and SK. Formal analysis: SL and SK. Methodology: SL and SK. Project administration: SL, SKH, YJL, HWB, and SK. Visualization: SL, SKH, YJL, HWB, and SK. Writing - original draft: SL and SK. Writing - review & editing: SL, SKH, YJL, HWB, and SK.

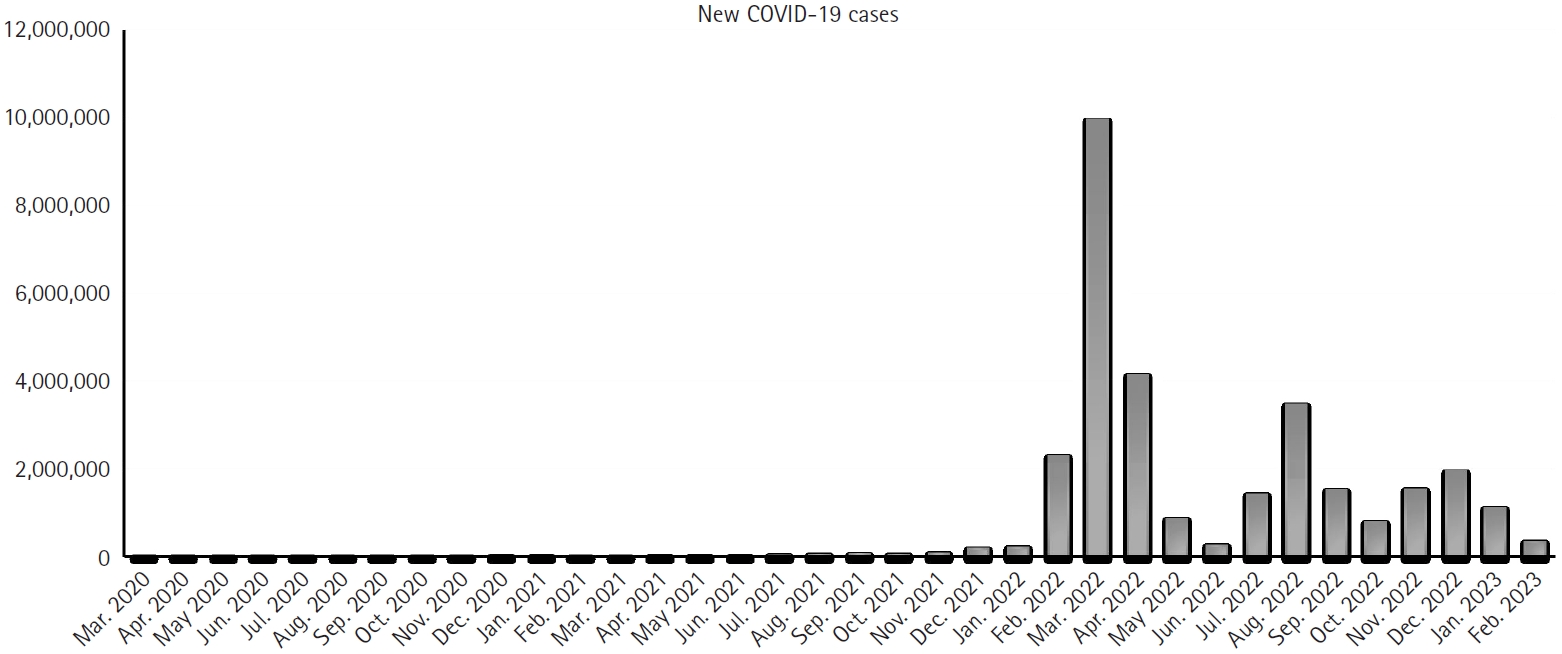

Fig. 1.

Table 1.

Table 2.

Table 3.

Table 4.

Table 5.

References

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- 99 View

- 1 Download

- Related articles in Ann Child Neurol

-

Impact of Weather on Prevalence of Febrile Seizures in Children2018 December;26(4)

Clinical Features of Moyamoya Disease in Children.2007 November;15(2)

Clinical Analysis of Sleep Disorders in Korean Children.2010 May;18(1)

Clinical Review of the of Seizures among Children.2010 November;18(2)