Diagnosis of Neuralgic Amyotrophy in an Adolescent Girl Using Magnetic Resonance Neurography: A Case Study

Article information

Neuralgic amyotrophy (NA) is characterized by severe acute pain around the shoulder, followed by upper extremity weakness and muscle atrophy. NA often occurs after triggering events, such as viral or bacterial infection, vaccination, or surgery. Although rare in children, it has been reported in individuals as young as 7 weeks old [1-3]. NA is not well-known among pediatricians and has seldom been reported in the pediatric population. Physicians often fail to recognize it, contributing to a mean delay of 3 to 9 months before diagnosis. This diagnostic delay can result in delayed treatment and a poor prognosis [2-4]. Although NA is more commonly observed in adults, pediatricians should be aware of this condition to prevent any delay in diagnosis. In this report, we present the case of an adolescent girl with NA who was diagnosed using magnetic resonance neurography (MRN) and recovered well after steroid treatment. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Daegu Catholic University Medical Center (CR-23-048). The requirement for publication consent was waived because personally identifiable protected health information was not disclosed in this report.

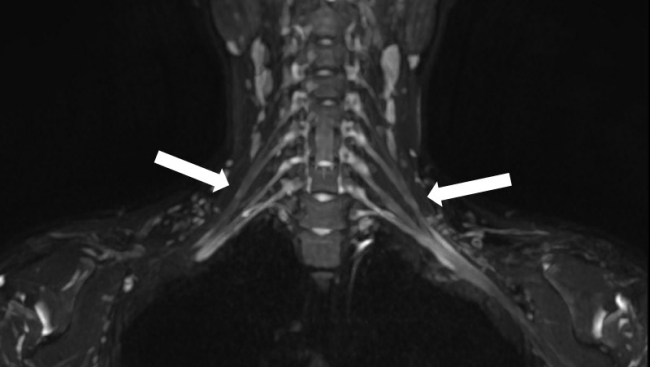

A 14-year-old girl presented with pain, swelling, and limited motion of the left arm. Six days prior, she had received an influenza vaccine in her left upper arm. Later that day, she experienced sudden, excruciating pain in her left upper extremity. She consistently felt pain and a tingling sensation from her shoulder to her fingertips. Her pain worsened, particularly in the evening, preventing her from falling asleep. She also reported being unable to move her left upper extremity. The patient denied having a fever, neck pain, difficulty breathing, or any history of trauma to her neck or arms. Her left arm and fingers had limited motion due to pain. The Medical Research Council grades for motor power in her left upper extremity were as follows: grade 5 for shoulder abduction and adduction; grade 4 for elbow flexion, elbow extension, and wrist flexion; and grade 3 for wrist extension, finger flexion, and finger extension. The sensory examination of her left upper extremity was intact, and deep tendon reflexes were normoreflexic. On day 10 after symptom onset, we performed electrodiagnostic studies (EDs) and MRN of the brachial plexus. EDs revealed no electrophysiological evidence of polyneuropathy, radiculopathy, or myopathy. MRN of the brachial plexus showed mild swelling in the C7, C8, and T1 nerve roots, trunk, division, and cord level of the bilateral brachial plexuses, more prominent on the left side, on coronal maximum intensity projection three-dimensional short tau inversion recovery (STIR) CUBE imaging (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI, USA) (Fig. 1). Bilateral brachial plexitis was diagnosed. On the 13th day after symptom onset, the patient began treatment with oral steroids, gabapentin, and physical therapy. By the second weekly follow-up, her condition had almost fully recovered. She reported no pain but experienced mild weakness in wrist extension, finger extension, and finger flexion.

Magnetic resonance neurography of the brachial plexus revealed mild swelling in the C7, C8, and T1 nerve roots, trunk, division, and cord level of the bilateral brachial plexuses, predominant on the left side (arrows), as seen on coronal maximum intensity projection three-dimensional short tau inversion recovery CUBE imaging (GE Healthcare).

NA is a rare, self-limited, painful neuropathy that typically occurs following a viral illness or immunization and is also known as Parsonage-Turner syndrome or idiopathic brachial neuritis [2,4,5]. Although NA is primarily unilateral, occasional subclinical contralateral limb involvement may be observed, as noted in the present case [1]. The exact cause of NA remains unknown, but it is generally believed to be an immune-mediated inflammatory reaction. Apart from infancy, when NA is associated with osteomyelitis and septic arthritis, this condition often occurs after triggering events [1,3,4,6]. In the present case study, the patient developed symptoms following an influenza vaccination on the same day. Despite the short time interval between vaccination and symptom onset, the condition may be attributed to an immune-mediated reaction to the vaccine. NA begins with acute neurological pain that extends from the shoulder or neck to the arm and hand. The pain is severe, excruciating, and described as throbbing or burning. It typically worsens at night or after rest and does not respond to usual analgesic treatments. This onset of pain is followed by muscle weakness, which usually occurs within the 1st day or week, although it can also develop in the 2nd week or later in some patients. Muscle atrophy subsequently occurs within 2 to 5 weeks [1,2]. Diagnosis of NA primarily relies on the clinical history and physical findings. EDs have limited value in establishing a diagnosis and can be normal in the early course of the disease despite the presence of clinical symptoms. Conventional magnetic resonance imaging of the brachial plexus may be helpful by demonstrating abnormalities in the affected muscles of patients with NA and ruling out focal pathology. However, it does not establish the diagnosis, nor does a normal brachial plexus study preclude it [1-4,6]. MRN is an optimized method for diagnosing NA because it can visualize the entire brachial plexus and assess the condition of the muscles innervated by the brachial plexus. Recently, MRN and high-resolution ultrasound (HRUS) have emerged as useful and valuable diagnostic tools in the acute phase of NA. Compared to MRN, HRUS is more convenient and better at revealing nerve abnormalities [5,7,8]. Ripellino et al. [7] found that MRN and HRUS showed nerve abnormalities within 1 month from the onset of NA in 90% of patients. The affected plexus nerves can exhibit increased signal intensity, enlargement, loss of fascicular pattern, or perineural edema on T2-weighted and STIR images [5]. Notably, intrinsic hourglass-like constrictions of involved nerves or nerve fascicles, an emerging diagnostic biomarker of NA, can be detected in the early phase. These pathological findings on MRN and HRUS can help predict prognosis and guide further management, such as surgical intervention [7,8]. Treatment of NA is symptomatic and typically involves a combination of corticosteroids, analgesics, immobilization, and physical therapy. Administering prednisolone in the 1st month of the acute phase appears to improve outcomes [9]. Currently, a 2-week corticosteroid therapy regimen is recommended in the early phase of NA for both children and adults [1,3,4]. The prognosis of NA is generally considered favorable, with full recovery reported in 80% to 90% of patients within 2 to 3 years following symptom onset [2,4]. In children, this condition has rarely been reported, with varying outcomes. Van Alfen et al. [10] suggested that the prognosis is poorer in children than in adults, despite the lower frequency of both pain and bilateral plexus involvement. However, Host and Skov [3] found that 63% of children with NA fully recovered in 8 months and 25% experienced partial recovery, indicating a better prognosis in children than previously anticipated. Although MRN facilitates rapid diagnostic confirmation, the patient’s history and a thorough clinical examination remain the cornerstones of NA diagnosis [4,7]. Due to its rarity and unfamiliarity among pediatricians, NA is often underdiagnosed or misdiagnosed, leading to diagnostic delays [2,4]. Regarding prognosis, full recovery may take several years, and 13% to 25% of patients may not recover at all, which can be disheartening for patients and parents [3,10]. Timely steroid administration can hasten recovery, making early diagnosis crucial for a favorable prognosis [9].

The present patient was diagnosed with NA using MRN. Her rapid recovery may be attributed to the early administration of steroids. Consequently, pediatricians should be cognizant of NA to avoid delayed diagnosis and treatment, and they should consider NA in the differential diagnosis for pain and weakness in the upper extremity.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: SMY and KHL. Data curation: SMY and YHK. Formal analysis: SMY and YHK. Methodology: SMY, YHK, and KHL. Project administration: KHL. Visualization: SMY and YHK. Writing - original draft: SMY. Writing - review & editing: KHL.