|

|

- Search

| Ann Child Neurol > Volume 31(4); 2023 > Article |

|

Neurocutaneous disorders primarily affect the central and peripheral nervous systems, as well as the skin, and can ultimately lead to the development of tumors in these organs. Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) is one of the most common neurocutaneous syndromes, with a reported incidence of approximately 1 in 2,600 to 1 in 3,000 individuals [1]. It is an autosomal dominant genetic disorder caused by pathogenic variants of the NF1 tumor suppressor gene located on chromosome 17q11.2 [2]. Inherited or de novo mutations in NF1 result in malfunctioning or loss of production of the tumor suppressor protein, neurofibromin, which eventually leads to various clinical manifestations. These manifestations include café-au-lait macules, axillary freckles, Lisch nodules, dermal neurofibromas, scoliosis, learning disabilities, attention deficits, brain tumors, and peripheral nerve tumors.

Chiari malformations comprise a group of disorders characterized by anatomical anomalies in the cerebellum, brainstem, and craniocervical junction, as described and classified by John Cleland and Hans Chiari [3]. Arnold Chiari type 1 malformation (CMI) is one of the four types of Chiari malformations, distinguished by abnormally displaced cerebellar tonsils below the level of the foramen magnum. Additional manifestations that may be sporadically observed in individuals with CMI include spinal cavitation, such as syringomyelia or syringohydromyelia, atlas assimilation, and hydrocephalus, occurring at varying frequencies [4]. The pathogenesis of Chiari malformations remains a subject of debate; however, it is generally considered to be a neuroectodermal or mesodermal defect.

The clinical manifestations of CMI can range from asymptomatic to symptoms such as elevated intracranial pressure, cranial neuropathies, myelopathy, cerebellar dysfunction, neck pain, and occipital headache. Retrospective studies have also shown associations between CMI and other conditions, such as NF1, Robin sequence [5], and Noonan syndrome [6]. Since 1986, there have been a limited number of case reports on the co-occurrence of NF1 and CMI, with some studies identifying CMI in approximately 5% to 9% of individuals with NF1 [7,8]. In this report, we present a pediatric case of NF1 and CMI, highlighting the importance of special attention to this rare combination.

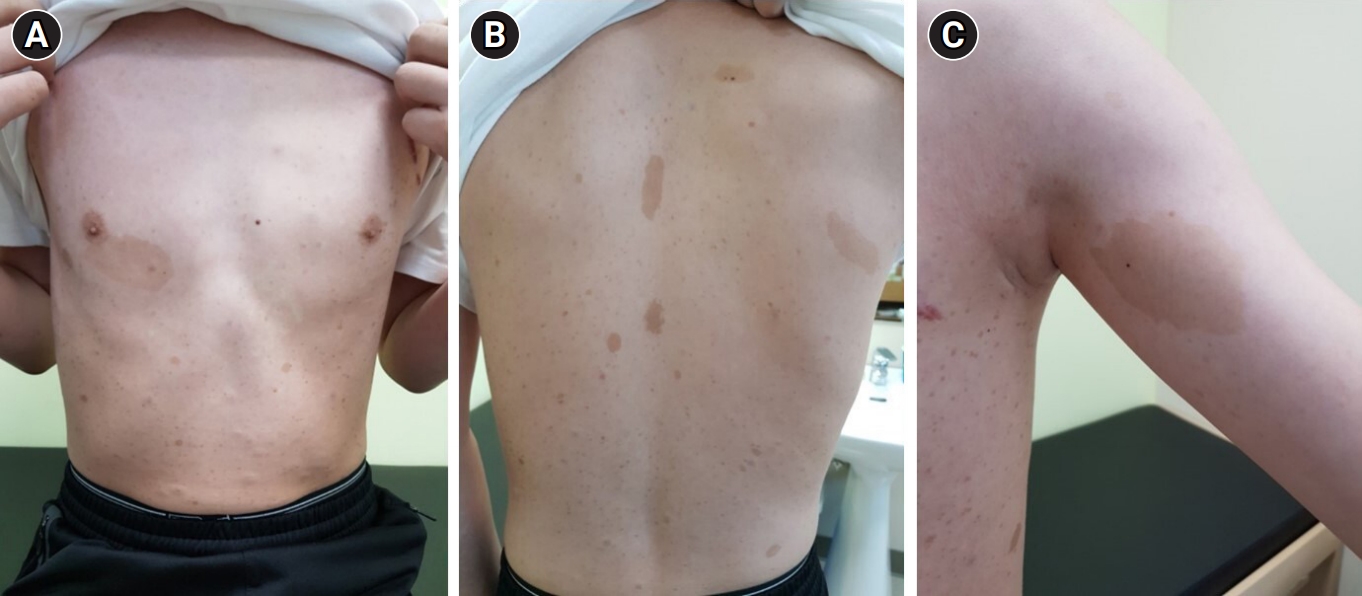

A 5-year-old boy presented to the dermatology clinic in our center with complaints of multiple brownish macules covering his entire body, including the abdomen, back, and extremities, freckles in both axillae, and a few skin-colored nodules on his back. These lesions initially appeared on his trunk and lower extremities when he was 5 months old and subsequently spread throughout his body. His medical and family histories were unremarkable, and he did not display any neurological symptoms. A histopathological examination of a skin biopsy taken from one of the macules revealed neurofibroma. Consequently, he was diagnosed with NF1, both clinically and histopathologically.

The patient was referred to a pediatric neurology clinic, where craniospinal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed T2 high signal intensity lesions in both basal ganglia. These lesions were consistent with the hamartomatous changes commonly observed in patients with NF1. Additionally, MRI showed mild herniation of the cerebellar tonsils and syringohydromyelia at the C6-7 to T1 levels, which were suggestive CMI.

The patient was subsequently referred to an ophthalmologist due to suspected eye complications. An ophthalmologic examination identified Lisch nodules on both irises, but no other ocular issues were detected.

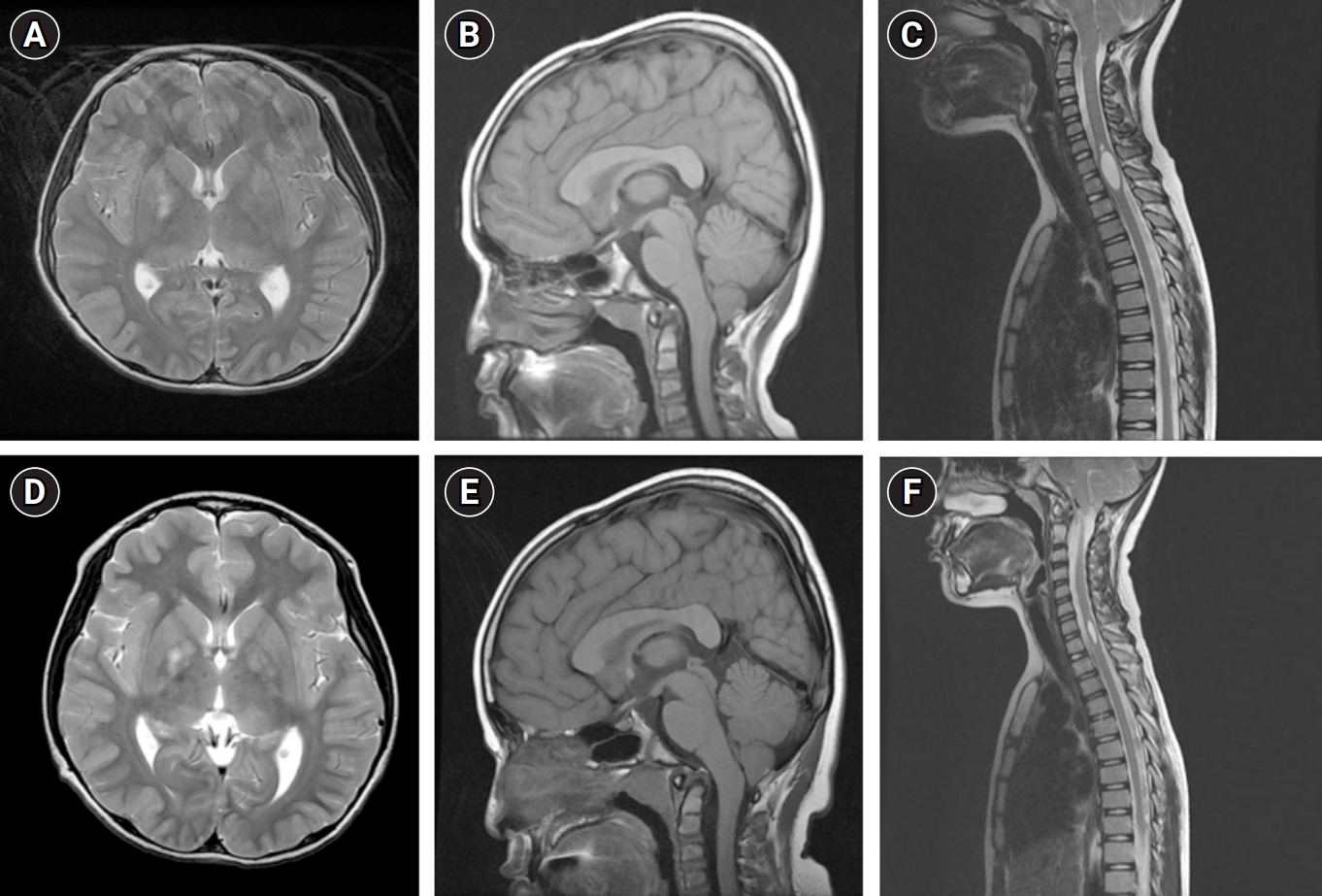

When the patient revisited the pediatric neurology clinic after 3 years, as advised in the absence of any new symptoms, craniospinal MRI exhibited no specific interval change compared to the previous examination (Fig. 1A-C). Furthermore, normal growth and development were observed. The patient was then advised to return for a follow-up visit in another 3 years.

At the age of 9 years, the patient unexpectedly returned to the pediatric neurology clinic, complaining of intermittent episodes of perioral muscle twitching lasting for about an hour and episodes of feeling spaced out with general weakness for a couple of seconds, both of which had started 3 months prior. Electroencephalography (EEG) revealed very frequent spike discharges from the left and/or right frontoparietal areas, occasional generalized bursts of spikes, and repetitive 2.5 Hz spike and wave discharges during the waking state. A follow-up brain MRI showed no significant interval changes in the T2 hyperintense lesions in both thalami, brainstem, and both cerebellum, but a slightly increased extent of T2 hyperintense lesions in both globus pallidus compared to previous evaluations. Additionally, there was no significant change in the mild herniation of cerebellar tonsils, which was suggestive of CMI (Fig. 1D-F). The patient was started on valproate with biannual follow-up EEG evaluations, which ultimately controlled the seizure activity.

In 2020, at the age of 12 years, the patient was evaluated by a multidisciplinary team at our center, which included experts in genetics, ophthalmology, pediatric cardiology, psychiatry, orthopedics, endocrinology, and neurology. At that time, medical photographs of the patient were taken and documented (Fig. 2). Direct sequencing of the NF1 gene revealed a heterozygous variant (c.6408_6418del) on exon 42, which was classified as a pathogenic variant according to the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG) criteria, thus confirming the genetic diagnosis. Although transthoracic echocardiography showed no abnormalities in cardiac function or structure, regular blood pressure check-ups were advised due to the potential for hypertension and vasculopathy in patients with NF1. No abnormal findings were observed during psychiatric consultations, and the patient demonstrated a normal intelligence quotient as assessed during regular school check-ups. Additionally, a slight decrease in bone density was detected during a bone mineral density evaluation, prompting the initiation of vitamin D supplementation. To date, the patient has been doing well without any major complaints or symptoms under the care of the multidisciplinary team.

NF1 is a hereditary disorder that presents a wide spectrum of symptoms and manifestations, ranging from pigmentary lesions to more severe complications, such as malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors [9]. Given that the disease can impact multiple organ systems, it is advised that patients undergo periodic evaluations by a multidisciplinary team of medical specialists, including ophthalmologists, cardiologists, neurologists, and endocrinologists.

Since the National Institutes of Health established the diagnostic criteria for NF1 in 1988 and recently revised them, these criteria have become the most specific and sensitive tool for diagnosing NF1 [10]. However, it is important to consider some uncommon comorbidities, such as CMI in rare cases. The anatomic anomalies observed in CMI may be associated with symptoms like severe headaches and could necessitate surgical intervention. Therefore, we recommend that physicians maintain a high level of suspicion. Further research is needed to elucidate the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying the combination of these two disease entities.

This study received approval from the Research Ethics Committee at Inha University Hospital (approval number: 2023-03-011-000). Due to the retrospective nature of the study, the need for written informed consent was waived.

Conflicts of interest

Young Se Kwon is the president of the Korean Child Neurology Society, but had no role in the decision to publish this article. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Notes

Author contribution

Conceptualization: HYR, SWY, WRJ, and YSK. Data curation: HYR, SWY, WRJ, and YSK. Formal analysis: HYR, SWY, and YSK. Funding acquisition: YSK. Project administration: HYR and YSK. Writing-original draft: HYR and YSK. Writing-review & editing: HYR, WRJ, and YSK.

Fig. 1.

Brain and whole spine magnetic resonance imaging in 2016 at the age of 8 years (A, B, C) and in 2017 at the age of 9 years (D, E, F) exhibiting characteristics of neurofibromatosis type 1 and Chiari type 1 malformation. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in 2016 at the age of 8 years showed T2 high signal intensity lesions in both basal ganglia which were consistent with the hamartomatous changes observed in that of patients with neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) (A). Mild herniation of cerebellar tonsils (B) and syringohydromyelia at the C6-7 to T1 levels shown on whole spine MRI (C) were suggestive of combined Chiari type 1 malformation (CMI). Brain MRI in 2017 at the age of 9 years showed a slight increase of extent of T2 hyperintensity of lesions in both globus pallidus compared to the previous evaluations. (D) There were no significant changes in the mild herniation of cerebellar tonsils (E) and syringohydromyelia on whole spine MRI (F).

Fig. 2.

(A) Medical photographs of the patient recorded in 2020 at the age of 12 years. Multiple Café-au-lait spots are visible on his chest and trunk with a largest one measured 6 x 3 cm below the right nipple. (B) Various sized café-au-lait spots on back with small ones of which sizes about 5 x 5 mm and big one on the midline of the back with a size of 5 x 2 cm. (C) A big café-au-lait spot and freckles on left axilla.

References

1. Evans DG, Howard E, Giblin C, Clancy T, Spencer H, Huson SM, et al. Birth incidence and prevalence of tumor-prone syndromes: estimates from a UK family genetic register service. Am J Med Genet A 2010;152A:327-32.

2. Gutmann DH, Ferner RE, Listernick RH, Korf BR, Wolters PL, Johnson KJ. Neurofibromatosis type 1. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017;3:17004.

3. Pearce JM. Arnold chiari, or "Cruveilhier cleland Chiari" malformation. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2000;68:13.

4. Grazzi L, Andrasik F. Headaches and Arnold-Chiari syndrome: when to suspect and how to investigate. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012;16:350-3.

5. Lee J, Hida K, Seki T, Kitamura J, Iwasaki Y. Pierre-Robin syndrome associated with Chiari type I malformation. Childs Nerv Syst 2003;19:380-3.

6. Holder-Espinasse M, Winter RM. Type 1 Arnold-Chiari malformation and Noonan syndrome. A new diagnostic feature? Clin Dysmorphol 2003;12:275.

7. Tubbs RS, Rutledge SL, Kosentka A, Bartolucci AA, Oakes WJ. Chiari I malformation and neurofibromatosis type 1. Pediatr Neurol 2004;30:278-80.

- TOOLS

-

METRICS

-

- 0 Crossref

- Scopus

- 2,406 View

- 41 Download

- Related articles in Ann Child Neurol

-

A Case of Neurofibromatosis Type 1 with Cortical Dysplasia.2005 November;13(2)

A Case of Neurofibromatosis Type I with Osteogenesis Imperfecta Type I.2006 November;14(2)