Distinctive Severe Ocular Abnormalities and Epilepsy Accompanied by a Novel ZEB2 Mutation in a Child with Mowat-Wilson Syndrome

Article information

Mowat-Wilson syndrome (MWS, OMIM #235730) is a rare genetic disorder that affects multiple organs, including the brain, heart, bowel, and eyes. It is caused by a heterozygous mutation of the zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2) gene. This syndrome is characterized by distinct facial features with various anomalies, including congenital megacolon, congenital heart defects, genitourinary malformation, dysgenesis of the corpus callosum, intellectual disability, and epilepsy [1,2]. Structural eye abnormalities are associated with MWS, but have rarely been reported [3-5]. Herein, we present the first reported case of MWS where prosthetic eye insertion was performed without enucleation, due to severe bilateral microphthalmos and permanent vision loss in a patient diagnosed with MWS associated with a novel de novo ZEB2 mutation.

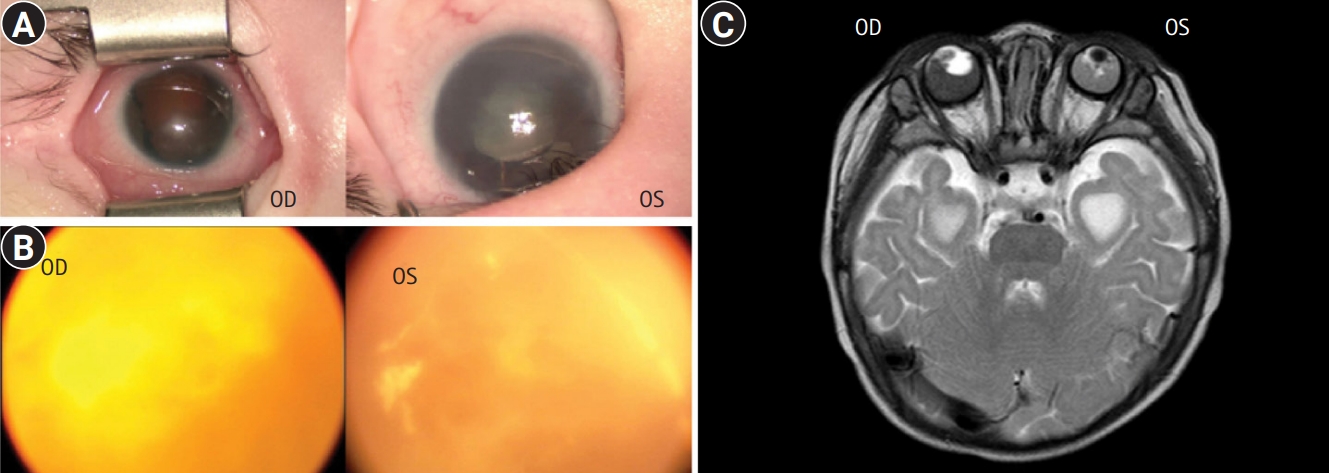

The patient was a male born at 38 weeks of gestation with a birth weight of 2.8 kg (10th percentile) and occipitofrontal-circumference (OFC) of 32 cm (10th percentile). He had no known family history of genetic diseases. His parents were nonconsanguineous and healthy, and his only sibling, an older sister, was healthy as well. The antenatal examination results were normal. At birth, he was admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit for abdominal distention and failure to pass meconium; he underwent surgery for congenital megacolon 1 week later. In addition, the neonatologist detected a heart murmur, bilateral microphthalmos, and hypospadias. He was referred to a quaternary center for further evaluation and treatment. Echocardiography showed mild stenosis of both branches of pulmonary arteries with hypoplasia, atrial septal defect, and patent ductus arteriosus (diameter, 1.3 to 1.8 mm). A detailed examination of the corneas (Fig. 1A) and wide-angle photography of the fundus (Fig. 1B) showed bilateral iris and retinal colobomas, hemorrhages, and corneal opacity. Orbital magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed bilateral hemorrhage and hypointense foci within a tumorous lesion, suggesting possible retinoblastoma on the right eyeball and atrophy of the left eyeball (Fig. 1C). Genetic tests for Axenfeld-Rieger syndrome and retinoblastoma were performed based on the patient’s severe eye abnormalities and an ocular mass. However, no paired like homeodomain 2 (PITX2) or RB transcriptional corepressor 1 (RB1) gene mutations were identified via Sanger sequencing. Brain MRI revealed corpus callosum dysgenesis with ventricular temporal horn enlargement. Despite the uncertain diagnosis, he started undergoing systemic chemotherapy at 7 months of age because the expected prognosis of retinoblastoma was poor. Treatment was discontinued after the third round of chemotherapy when he was 8 months old because there was no significant change in the orbital lesion. His best-corrected visual acuity revealed no light perception in both eyes at 9 months of age. His development occurred at a significantly slower rate than normal, and he remained mute. He underwent regular assessments and rehabilitation therapy according to his developmental stage for 2 years.

Eye abnormalities in a patient with Mowat-Wilson syndrome with a novel zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2) mutation. Detailed examination of the corneas (A) and wide-angle photography of the fundus (B) of the right (oculus dexter [OD]) and left (oculus sinister [OS]) eyes. Bilateral iris and retinal colobomas, hemorrhages, and corneal opacity were observed. (C) Orbital magnetic resonance imaging shows bilateral hemorrhage and hypointense foci within a tumorous lesion suggesting possible retinoblastoma on the right eyeball (OD) and atrophy of the left eyeball (OS).

The patient first visited the pediatric neurology division of a tertiary hospital when he was 3 years old, in November 2017, for new-onset myoclonic and generalized tonic seizures. He was noted to have short stature (height: 90 cm, less than the 3rd percentile), microcephaly (OFC of 42 cm, less than the 3rd percentile), and facial dysmorphism with a long face, high forehead, widely spaced eyes, phthisis, and a prominent but narrow triangular pointed chin. All five aspects—gross motor, fine motor, language, cognition, and social-emotional—of his development were severely delayed. Electroencephalography revealed slow and disorganized background rhythms with multifocal spikes, diffuse spikes, and wave discharges.

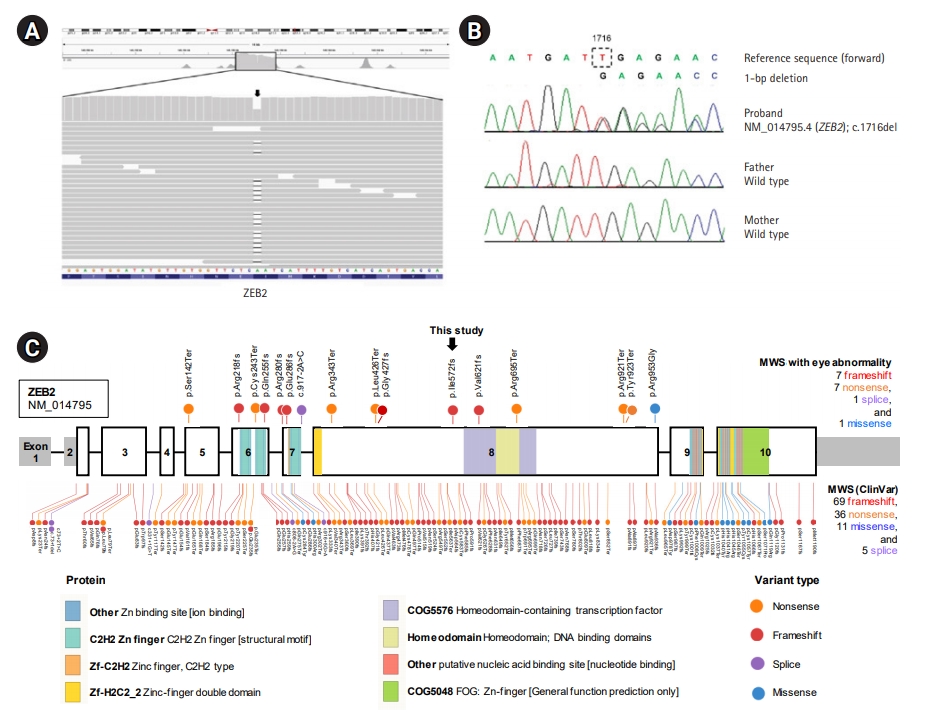

We performed whole-exome sequencing for a genetic diagnosis of this patient and his parents. A deletion variant (c.1716del [p.Ile572MetfsTer35]) was identified in ZEB2 (RefSeq accession number NM_014795.4) (Fig. 2A). We validated this variant by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 2B). The variant was predicted to result in a frameshift and premature termination of the ZEB2 protein. This variant has not been reported previously and has not been found in 1,722 individuals of Korean descent [6]. According to the international guideline for variant interpretation [7], this variant is classified as pathogenic based on one very strong piece of evidence (null variant), one strong piece of evidence (de novo occurrence), and one moderate piece of evidence (absent from controls). We did not find any other strong candidate genes in the results of exome sequencing. Due to severe microphthalmos and poor vision, the patient was prescribed ocular prostheses without enucleation at 5 years of age. The patient is currently 6 years old and continues to take two antiepileptic drugs (valproic acid and zonisamide) for his atypical absence, focal, and myoclonic seizures. He can stand with support and continues to develop slowly.

Genetic study of a Mowat-Wilson syndrome patient with severe eye abnormalities. (A) Integrative Genomics Viewer snapshot of a novel pathogenic zinc finger E-box binding homeobox 2 (ZEB2) variant identified by exome sequencing (arrow). (B) Sequence chromatograms show a heterozyous frameshift variant (c.1716del; p.Ile572MetfsTer35) of ZEB2 in the proband and normal sequences in his unaffected parents (de novo mutation). (C) Mutational landscape of ZEB2 in Mowat-Wilson syndrome (MWS) patients. The sites newly identified in this study and previously reported pathogenic variants in MWS patients with eye abnormality are indicated above the bar. Sites of previously reported pathogenic/likely pathogenic variants in MWS patients listed in the ClinVar database (Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor [VEP] tool version 96, https://www.ensembl.org) are indicated below the bar. The bar represents the ZEB2 gene, and the numbers indicate the exons (sized to scale) with noncoding sequences shaded. This comprehensive visualization of the pathogenic variants was performed with ProteinPaint (http://pecan.stjude.org).

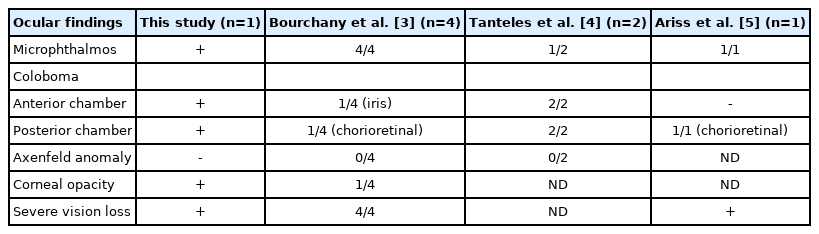

Microphthalmos is a severe ocular developmental defect characterized by reduced eyeball size. Coloboma, considered a part of the microphthalmos spectrum, is caused by the failure of the ectodermal optic vesicle fissure to close [8]. Wide genetic heterogeneity, including genes such as SRY-box transcription factor 2 (SOX2), paired box 6 (PAX6), orthodenticle homeobox 2 (OTX2), retina and anterior neural fold homeobox (RAX), and visual system homeobox 2 (VSX2), has been associated with these anomalies, and each gene causes syndromic or non-syndromic single-gene disorders. These structural eye abnormalities can overlap with the ophthalmologic findings of other congenital disorders such as CHARGE (coloboma, heart anomaly, choanal atresia, retardation, genital, and ear anomalies) syndrome, Axenfeld-Reiger syndrome, and Coats disease, hindering the diagnosis of MWS [2,8]. Our report described the clinical course and manifestation of a rare case of MWS with severe eye abnormalities. We also contributed to the understanding of the ocular findings by adding a detailed description and comparing our patient to previously described MWS patients with eye abnormalities (Table 1) [3-5].

Comparison of eye abnormalities of the patient in this study and those in previous studies of Mowat-Wilson syndrome

To date, a total of 121 disease-causing variants of ZEB2 responsible for MWS have been reported worldwide in the ClinVar database (Ensembl Variant Effect Predictor [VEP] tool version 96, https://www.ensembl.org). Most involve frameshift (57%, 69/121), nonsense (30%, 36/121), missense (9%, 11/121), and splice-site (4%, 5/121) mutations randomly distributed throughout the ZEB2 protein (Fig. 2C). No data have been reported for genotype-phenotype correlations regarding eye abnormalities. However, the pathogenic variants in MWS patients with eye abnormalities, including the newly identified variant in this study, exhibit a similar spectrum of mutation types (with frameshift and nonsense being most frequent) and are distributed in exons 5 to 8 of the ZEB2 gene (Fig. 2C).

The clinical diagnosis of MWS can be challenging because of the variable phenotypic presentation and limited information about the rare accompanying eye abnormalities [3]. This report contributes to a better understanding of the genetic background of patients with MWS who have associated eye abnormalities.

This case was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Soonchunhyang University Bucheon hospital (2017-05-032). The patient’s legal guardians provided written informed consent.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: SP and MAJ. Data curation: JSY and MAJ. Formal analysis: SP. Methodology: YJH. Visualization: SP and JSY. Writing-original draft: SP and MAJ. Writing-review & editing: YJH and MAJ.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (2017R1C1B5018081).