Risk Factors for Seizures after Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Pediatric Hemato-Oncologic Patients: A Single Tertiary Center Study in the Republic of Korea

Article information

Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to assess the incidence of seizures, clinical manifestations, and risk factors that could predict the occurrence of seizures after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in children.

Methods

The study group consisted of 543 patients (311 males and 232 females) registered at the Catholic University of Korea’s Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital who received HSCT before the age of 18 from January 2009 to January 2019. Their medical records and test results were retrospectively reviewed.

Results

The incidence of seizure after HSCT was 6.6% and the average age of seizure patients was 8.33±5.5 years. The use of calcineurin inhibitors combined with methotrexate as prophylaxis for graft versus host disease (GVHD) was a statistically significant risk factor for seizures (P=0.006). Pediatric patients with grade 2–4 acute GVHD (P=0.003) also showed a higher incidence of seizures than those with grade 0–1 acute GVHD after HSCT.

Conclusion

Our findings indicate that among pediatric patients who underwent HSCT, using calcineurin inhibitors with methotrexate as a conditioning regimen and a higher grade (≥2) of acute GVHD are risk factors of seizures.

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) is widely used as a complete cure for patients with reduced bone marrow function due to various malignancies (such as leukemia, malignant lymphoma, and solid neoplasms) and some nonmalignant conditions (such as severe aplastic anemia, sickle cell disease, thalassemia, immune disorders, certain metabolic disorders, and severe refractory autoimmune diseases) [1]. The HSCT procedure consists of infusing hematopoietic stem cells after a short course of high-dose chemotherapy that is frequently associated with total body irradiation (TBI) to suppress the host immune system in order to prevent graft rejection. HSCT often places patients at risk of life-threatening complications throughout the course of treatment and beyond. Despite significant improvements in peri-transplant treatment, neurological complications—especially those involving the central nervous system (CNS)—along with many other complications, such as graft rejection or graft failure, thrombocytopenia, metabolic disturbances, chemotherapy/radiotherapy-induced toxicity, infection, and graft versus host disease (GVHD), remain contributors to morbidity and mortality during the post-HSCT period [2-4]. The total incidence of neurological complications after HSCT has been reported to range from 8% to 70% [5,6]. Seizure is the most common clinical manifestation of neurological complications [7,8], and younger people have a higher risk of seizures than adults after HSCT [9]. However, only a few studies have analyzed differences between patients with seizures and those without seizures and risk factors for seizures after HSCT, especially in the pediatric population. The aim of this study was to evaluate the frequency, clinical features, and risk factors of seizures to identify information that could be used to prevent seizures and improve the prognosis of pediatric patients after HSCT.

Materials and Methods

1. Patients

The study group consisted of 543 patients (311 males and 232 females) registered at the Catholic University of Korea’s Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital who received allogeneic (506 patients) or autologous (37 patients) HSCT before the age of 18 as treatment for malignancies or other non-malignant hematologic diseases from January 2009 to January 2019.

We retrospectively reviewed the records of all patients who underwent at least one neurological diagnostic test, including brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and electroencephalography (EEG), after HSCT. We also reviewed records of demographic characteristics, including patients’ age, sex, underlying disease, type of HSCT, conditioning regimen (including TBI, busulfan administration, or both), and grade of acute GVHD. The diagnosis of acute GVHD was based on the Glucksberg Seattle criteria [10]. Patients were divided into those younger than 5 years and older than 5 years based on the age at the time of HSCT. This study group was monitored for at least 6 months. Among the 36 patients who experienced seizures, seven patients with a preexisting history of seizures before HSCT were excluded from this study.

2. Type of HSCT

HSCT procedures can be classified into two types: (1) allogeneic HSCT, which uses hematopoietic stem cells harvested from a donor; and (2) autologous HSCT, which uses hematopoietic stem cells harvested from the patient’s bone marrow or peripheral blood.

3. Conditioning regimen

All patients received pre-transplantation conditioning treatment based on the underlying disease according to the transplant program protocol. In this study, we divided the type of conditioning regimen as follows, regardless of overall intensity: TBI-based, busulfan-based, TBI and busulfan-based, and others.

4. Prophylaxis for GVHD

As prophylaxis for GVHD, calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine, tacrolimus) with or without methotrexate (MTX), antithymoglobulin, and a steroid were administered according to the institutional protocol.

5. Clinical profiles of seizures

The diagnosis of seizures was based on clinical manifestations and neurological/physical examination findings, laboratory findings, EEG findings, and brain MRI conducted at the time of the seizures. Seizure types were classified according to the 2017 International League against Epilepsy criteria. The timing of seizures was classified into three categories according to three phases of immune status, since the timing of neurological complications is similar to the timing of complications in other organs associated with the three phases of patient’s immune status after HSCT: (1) the pre-engraftment period (<30 days post-HSCT); (2) the early post-engraftment period (30 to 100 days post-HSCT); and (3) the later post-engraftment period (>100 days post-HSCT) [11]. Abnormalities on EEG included background abnormalities and abnormal epileptiform discharges. Epileptiform discharges were divided into focal and generalized depending on the region of the epileptic focus. The outcome of seizures included freedom from seizures, development of epilepsy, and death. Freedom from seizures was defined as a sustained seizure-free status for at least 12 months.

6. Statistical methods

Patients were classified into those with seizures and those without seizures. SSPS software version 24.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for all statistical analyses. Normally distributed variables are presented as mean±standard deviation. Univariate analysis was carried out to compare independent variables as risk factors for seizure after HSCT using the chi-square test. Statistically significant variables (P<0.05) in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression analysis.

Results

1. Characteristics of patients after HSCT

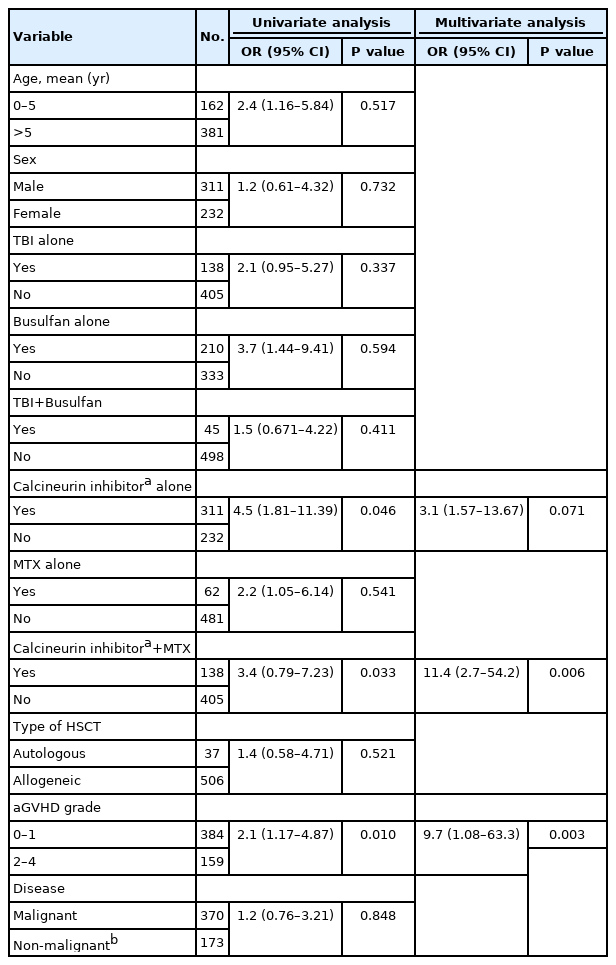

A total of 543 patients underwent HSCT, including 370 patients (69.3%) who had malignant diseases such as leukemia, lymphoma, and solid neoplasms and 173 patients (32.4%) who had non-malignant hematologic diseases (Table 1). A total of 506 patients received allogeneic HSCT and 37 received autologous HSCT. The average age of the patients was 8.88±5.5 years (range, 5 months to 18 years). There were 162 (29.8%) patients who were younger than 5 years and 381 (70.2%) patients who were older than 5 years (Table 1).

Comparision of characteristics between patients with and without seizures after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

There were 138 patients (25.4%) who received TBI-based conditioning regimens for HSCT, 210 patients (38.7%) who received busulfan-based regimens, 45 patients (8.3%) who received both TBI- and busulfan-based regimens, and 150 patients (27.6%) who received other regimens. For GVHD prophylaxis, 311 patients (57.3%) received calcineurin inhibitors, 62 patients (11.4%) received MTX, 138 patients (25.4%) received calcineurin inhibitors combined with MTX, and 32 patients (5.9%) received other immunosuppressants (Table 1).

2. Clinical characteristics of seizures after HSCT

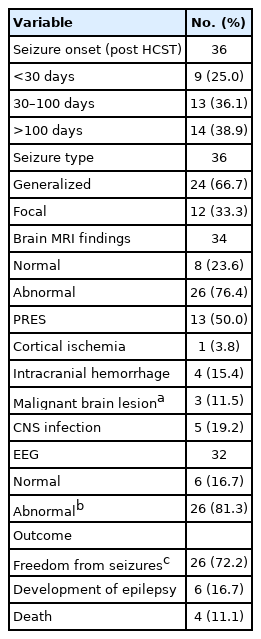

HSCT-associated seizures were observed in 36 of the 543 pediatric patients (Table 2). The incidence of seizures after HSCT was 6.6%. The average age of the seizure patients was 8.33±5.5 years. The ratio of male to female patients was 1.25:1 (20:16). The clinical characteristics of post-HSCT seizures are described in Table 2. Seizures were observed between 3 days and 18 months after HSCT, with nine patients (25.0%) having seizures within the pre-engraftment period, 13 patients (36.1%) having seizures between 30 and 100 days, and 14 patients (38.9%) having seizures after 100 days post-HSCT (Table 2). Generalized seizures were observed in 24 patients (66.7%), whereas focal seizures were observed in 12 patients (33.3%). Of the 36 patients who developed seizures, two patients did not undergo brain MRI due to unstable vital signs. Of the remaining 34 patients who underwent brain MRI, eight (23.6%) had normal results and 26 (76.4%) had abnormal results. Sepsis, cytomegalovirus meningitis, and metabolic imbalances including hyponatremia (<135 mM), hypokalemia (<3.5 mM), and abnormal liver function were observed in patients who showed normal brain MRI. The most frequent abnormal brain MRI finding was posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome (PRES; n=13, 50.0%), followed by CNS infection (n=5, 19.2%). Intracranial hemorrhage and cortical ischemia were present in four patients and one patient, respectively. Malignant brain lesions reflecting CNS involvement, including relapse or metastasis of original malignancies, were observed in three patients, and were also confirmed by a cerebrospinal fluid test. Post-ictal EEG was performed in 32 patients, of whom 26 (81.3%) had abnormal EEG results. Seventeen patients (65.4%) showed background abnormalities with diffuse slow waves, and nine patients (34.6%) had epileptiform discharges, including eight patients (30.8%) who showed focal epileptiform discharges and one patient (3.8%) who showed generalized epileptiform discharges.

Twenty-six of the seizure patients became seizure-free (72.2%) without requiring antiepileptic drugs, whereas six patients developed epilepsy and four patients died during follow-up.

3. Statistical analysis of seizures and risk factors

To analyze risk factors for developing seizures in HSCT patients, patients’ age at the time of seizures, sex, conditioning regimen, prophylaxis for GVHD, type of HSCT (allogeneic or autologous), grade of acute GVHD, and underlying disease were considered. The results of the univariate and multivariate analyses of significant risk factors are shown in Table 3.

Univariate and multivariate analysis of risk factors for seizures after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

1) Prophylaxis for GVHD

Of 449 patients who received a calcineurin inhibitor with or without other regimens as prophylaxis for GVHD, 30 (6.7%) developed seizures. In the univariate analysis, patients with calcineurin inhibitors alone were found to be more likely to have seizures (P=0.046) than those who received GVHD prophylaxis without calcineurin inhibitors alone, whereas multivariate analysis showed no significant difference in the risk of developing seizures between the two groups. However, patients using calcineurin inhibitors combined with MTX showed a higher risk of developing seizures than patients with other prophylaxis regimens (P=0.006).

2) Grade of acute GVHD

Among patients with acute GVHD, 19 (4.9%) out of 384 patients with grade 0–1 and 17 (10.7%) out of 159 patients with grade 2–4 developed seizures. Those with grade 2–4 acute GVHD had a higher risk of developing seizures than those with grade 0–1 acute GVHD (P=0.010). In the multivariate analysis, grade 2–4 acute GVHD remained a significant risk factor for seizures (P=0.003).

Discussion

Neurological complications associated with HSCT are important causes of morbidity and mortality in both children and adults. Most neurological complications are caused by the original disease or relapse, development of a secondary tumor, treatment-induced neurotoxicity including chemotherapy and TBI, CNS infection, cerebrovascular disease, and metabolic encephalopathy [6,9,12,13]. In our study, the incidence of seizures in children after HSCT was 6.6%, which is slightly lower than the incidence that we reported in the past (13.8%) [14]. This might be attributable to the improved treatment environment including prompt diagnosis and advanced prophylaxis/treatment of HSCT, including strictly controlled blood pressure and dose reduction or switching between calcineurin inhibitors to reduce drug-induced neurotoxicity. According to other studies, the incidence of seizures among HSCT patients varies from 1.6% to 15.4% [9,12]. This variability might be due to differences in patients, transplantation characteristics, duration of follow-up, and trial design.

Previous studies have identified high doses of TBI and chemotherapy (including calcineurin inhibitors, busulfan, and MTX) as risk factors for seizures after HSCT [15,16]. Calcineurin inhibitors (cyclosporine and tacrolimus) are commonly used immunosuppressants. They work by inhibiting T-lymphocyte activation and proliferation, but might increase the permeability of the blood-brain barrier (BBB), resulting in neurotoxicity [17]. In vitro and in vivo studies have reported that vasoconstrictive effects via activation of sympathetic outflow by calcineurin inhibitors might also increase the permeability of the BBB [17,18]. Comorbid conditions, including hypertension, infection, and metabolic disorders such as hypomagnesemia, might further exacerbate the permeability of the BBB [19,20]. Furthermore, calcineurin inhibitors may modulate neuronal excitation and neuronal inhibition (known to play an important role in seizures) by altering gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and N-methyl-D-aspartic acid (NMDA)–mediated responses via calcineurin [21]. The incidence of seizures caused by calcineurin inhibitors is generally less than 1%, although a previous study reported an incidence as high as 14.8% [22]. Although our results showed that the use of calcineurin inhibitors alone was not a statistically significant risk factor for seizure development, the fact that calcineurin inhibitor use combined with MTX did show statistical significance implicates calcineurin inhibitors as a risk factor for the development of seizures. A previous study also showed that calcineurin inhibitors, especially cyclosporine, combined with MTX in the regimen for prophylaxis of GVHD were a risk factor for seizures after HSCT [23], suggesting that cumulative exposure to immunosuppressants might exacerbate drug-induced neurotoxicity and susceptibility to CNS infection, thereby increasing the incidence of seizures.

Busulfan is frequently used in conditioning regimens for HSCT. It has therapeutic effects on the CNS, and it crosses the BBB freely [24]. However, it may cause neurotoxicity and result in seizures. The incidence of seizures in those who have received busulfan after HSCT ranges from 10% to 40% if anticonvulsants are not given [25]. In our study, 15 (5.9%) out of 255 patients who were administered busulfan in the conditioning regimen had seizures. However, none of them had seizures during the pre-treatment period for HSCT, possibly due to co-administration of phenytoin, which might have prevented busulfan-induced seizures.

During the pre-engraftment period (days 0–30), the patient’s immune system is completely suppressed. Due to high-dose chemotherapy with or without TBI as a result of the conditioning regimen for HSCT, the patient is vulnerable to severe infections [23]. In the early post-engraftment period (days 30–100), the patient’s immune system starts to recover. Acute GVHD may develop in this period. By 100 days after HSCT, the patient’s immune system continues to recover gradually, moving towards full recovery. Chronic GVHD may develop [11,26]. Our results showed that, by a narrow margin, the emergence of seizures mostly occurred after 100 days of HSCT. In the post-transplantation period, especially at 3 months after HSCT and beyond, an increased concentration of immunosuppressants (e.g., cyclosporine and corticosteroids) administered as prophylaxis/treatment for chronic GVHD can result in neurological complications [15], which may lead to the development of seizures.

We found that 83.3% (n=26) of all seizure patients had abnormalities on brain MRI, with PRES (n=13, 50.0%) being the most frequent abnormal finding. PRES has been reported to be one of the most common encephalopathies that contribute to the occurrence of seizures after transplantation [27,28]. The etiologies of PRES include hypertensive encephalopathy and treatment-related leukoencephalopathy, associated with both cranial irradiation and chemotherapy. Among 36 patients who experienced seizures in our study, 23 received cyclosporine to prevent and treat GVHD, and 17 of them showed a high blood concentration of cyclosporine (>250 ng/mL). Although the pathophysiology of PRES is not fully understood [29] cyclosporine-associated PRES has been related to high levels of cyclosporine [27]. In addition, 29 patients with seizures received corticosteroids for GVHD treatment, which is relevant because corticosteroids can alter cyclosporine levels, potentially leading to the development of neurological complications [30]. Twenty-four patients showed increased blood pressure during seizures, whereas 12 patients had stable vital signs. The patients with hypertension were also being treated with immunosuppressants (cyclosporine and corticosteroids), which are known to cause high blood pressure [19,29].

PRES can affect the white matter, particularly the subcortical white matter [31]. Although PRES is reversible and generally has a good prognosis, it can lead to permanent neurological deficits and an increased risk of mortality [23,32]. Furthermore, PRES seems to be associated with epilepsy diagnosis as a long-term consequence [33]. In our study, more than half of the patients (72.2%) who experienced seizures were seizure-free, and most of them only had a single seizure, whereas only a minority of patients needed prolonged antiepileptic drug therapy. Most patients had a favorable prognosis; however, in patients with some conditions (especially CNS infection and intracranial hemorrhage), recurrent seizures occurred.

In a prior study based on serial EEG examinations, more than 80% of children who experienced seizures after HSCT showed diffuse slow waves of background activity [16]. Other studies have found focal and generalized slow activity consistent with encephalopathy based on post-ictal EEG obtained in the first 48 hours after the first seizures in HSCT patients [34]. In our data, 81.3% of patients who developed seizures had abnormalities on post-ictal EEG and more than half of them showed slow background activity, suggesting cerebral dysfunction. This shows that EEG might be a helpful tool for detecting abnormalities in brain function (e.g., encephalopathy) in HSCT patients, especially in children with seizures.

In addition to the use of calcineurin inhibitors with MTX for GVHD prophylaxis, another independent risk factor identified by multivariate statistical analysis for developing seizures in this study was high-grade (>grade 2) acute GVHD, similar to the findings reported in other studies [9,34-36]. As a possible explanation, prolonged and increased doses of immunosuppression to control severe GVHD might have resulted in high susceptibility to CNS infection and drug-induced neurotoxicity, thereby contributing to seizures [37]. Although acute GVHD greater than grade 2 has been reported to cause neurological complications [16,35,36], little is known about its CNS involvement. Some animal studies support the likelihood of the brain being targeted for GVHD development due to increased expression of immune mediators in the brain parenchyma and cerebral vessels during GVHD [38]. Some clinical trials have also revealed the possibility of CNS involvement in GVHD by presenting inflammation in the brain without evidence of apparent infection [39].

In summary, in pediatric patients receiving HSCT for any reason, especially in patients receiving calcineurin inhibitors with MTX for GVHD prophylaxis and those with a higher grade (≥2) of acute GVHD with a high risk of seizures, close observation and intensive care seem to be necessary to improve clinical outcomes.

The limitations of our research include its retrospective design and the small number of subjects. Thus, more studies are needed in the future to confirm our findings.

Notes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

Author contribution

Conceptualization: JUM, JYL, JWL, NGC, BC, and IGL. Data curation: JUM. Formal analysis: JUM, JWL, NGC, BC, and IGL. Methodology: JUM. Writing-original draft: JUM. Writing-review & editing: JUM, JWL, and IGL.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Seoul St. Mary Hospital of Catholic University of Korea.