|

|

- Search

| Ann Child Neurol > Volume 29(1); 2021 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The criteria for discontinuing antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) in children with well-controlled epilepsy remain unclear. This study sought to identify the recurrence rate of epilepsy after the discontinuation of AEDs and the risk factors associated with recurrence.

Methods

We retrospectively reviewed the records of 441 children who discontinued AEDs at our department of pediatrics from August 2007 to July 2017. AED tapering was performed in patients who were seizure-free for more than 2 years after taking AEDs, and patients were monitored for 1 year after the discontinuation of AEDs.

Results

We found that 87 patients (87/441, 19.7%) experienced seizure recurrence within 1 year after the discontinuation of AEDs. Among them, 38 patients (38/87, 43.7%) experienced recurrence during AED tapering. The recurrence of seizures was related to the patient’s age at AED onset and when seizures were controlled, a history of seizure recurrence after previous discontinuation of AEDs or a seizure episode during AED administration, and no improvement of electroencephalographic (EEG) findings.

Conclusion

The recurrence rate within 1 year after the discontinuation of AEDs was almost 20%, and nearly half of the recurrences took place during the tapering period. We recommend caution when considering whether to discontinue AEDs in patients with a history of seizure recurrence after AED discontinuation, a seizure episode during AED administration, or no (or slight) improvement of EEG findings.

Epilepsy is a disease whose diagnosis and treatment are continuously undergoing development. Currently, epileptic symptoms can be controlled in 70% to 80% of affected patients with the administration of various antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) [1]. The rate of symptom recurrence is being increasingly diminished by the advancement of AEDs and drugs that can measure serum concentration [2]. However, AEDs are associated with poor drug compliance due to their numerous adverse effects and the need to consume them daily. These drawbacks are of particular concern for school-age children, in whom AEDs cause drowsiness, fatigue, and attention deficits that may impair their language and cognitive development [3].

Prior research has investigated whether the timing of discontinuing AED administration to pediatric patients can be calibrated so as to diminish the probability of seizure recurrence and, hence, the need to resume AED therapy [4]. For instance, Strozzi et al. [5] reported a seizure-free period of to 2 years to be suggestible for AED discontinuation. However, as only a few studies have considered the discontinuation of AEDs and the risk factors associated with seizure recurrence in children, the timing of AED discontinuation in pediatric patients remains controversial.

In this study, we sought to identify the recurrence rates of epilepsy after discontinuation of AEDs in pediatric patients. We also identified the risk factors associated with the recurrence of epilepsy.

The present retrospective analysis was conducting using data obtained from the patients’ medical records. Among the patients that were admitted to the Department of Pediatrics at the Jeonbuk National University Hospital of South Korea and diagnosed with epilepsy between August 31st 2007 and July 31st 2017, patients (except for neonatal children under 1 month) who showed two or more unprovoked attacks or who visited the hospital with 1st attack and showed clear abnormal findings related to clinical symptoms on electroencephalography (EEG) were selected as participants for this study. They administrated of AEDs for at least 2 years and monitored for 1 year after tapering of AEDs. EEGs obtained at the time of diagnosis and before the discontinuation of AEDs were analyzed and neuroimaging was tested in patients except 56 patients who failed sedation treatment, rejected examinations, or were presumed to be epilepsy syndrome in EEG findings

Since the timing of tapering AEDs depends on the type of epilepsy, we considered a seizure-free period as at least 2 years for types with good prognosis such as benign rolandic epilepsy, and more than 2 years for types with incurable prognosis such as infantile spasm or Lennox-Gastaut syndrome. However, we attempted to taper AEDs if there was a clear improvement in EEG or when the caregiver requested an end to treatment for their children whose epilepsy had been well-controlled for at least 2 years in types with incurable prognosis. AED tapering was carried out with a gradual and even drug dose reduction over a mean period of more than 8 weeks and if more than two medications were administered, one by one was reduced. All patients were monitored for 1 year after the discontinuation of AEDs.

The definition of recurrence of epilepsy was defined when there was unprovoked seizure within 1 year after the discontinuation of AEDs. However, it was determined that recurrence occurred when the typical 3 Hz spike-and-wave complex was shown on the follow-up EEG regardless of clinical symptoms in the case of absence seizure.

A total of 630 patients were initially selected for participation in this study. We subsequently excluded 42 patients with limited data due to them having been transferred from a different hospital after the initiation of AED treatment, 27 patients who were less than a month old upon admission, 82 patients who received less than 1 year of follow-up, and 38 patients who diagnosed with juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, which is known to recur soon after the discontinuation of AEDs. Data obtained from the final 441 patients were analyzed to identify the recurrence rates of epilepsy after discontinuation of AEDs and the risk factors associated with the recurrence.

This study was performed with approval from the Institutional Review Board of Jeonbuk National University Hospital Research Council (CUH2020-01-037). Written informed consent by the patients was waived due to a retrospective nature of our study.

We considered the association between epilepsy recurrence and the following factors associated with the recurrence: sex, age-related factors (the age at seizure onset, at which the AED administration began, at maintaining a longer interval than the existing seizure period [which seizures were controlled], and at discontinuation of AEDs), episodes of seizure during AED administration, number of AEDs administered, family history of epilepsy, history of febrile convulsion and status epilepticus, history of epilepsy recurrence after previous discontinuation of AEDs, pretreatment seizures frequency, radiographic abnormalities, EEG analysis, and neurological disability.

The SPSS version 25 (IBM Co., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to perform all statistical analyses. The risk factors for the recurrence of epilepsy were analyzed using the chi-square test, independentsamplest test, and Kaplan-Meier survival analysis with the log-rank test. Data are presented as the mean±standard deviation and P values <0.05 were considered to indicate statistical significance.

After the discontinuation of AEDs, 87 (19.7%) of 441 patients experienced recurrences within 1 year. Among 87 patients with recurrence within 1 year, 53 men and 34 women and 38 patients (43.7%) experienced recurrences during tapering period, 22 patients (25.3%) relapsed within 6 months after discontinuation of AEDs and 27 patients (31.0%) relapsed within 6 months to 1 year. The average time of recurrence after AED discontinuation was 0.7±1.0 year. Of these, 24.1% had recurrence after previous discontinuation of AEDs, 67.8% had episodes of seizure during AED administration, 65.5% used a single type of AED to control seizure, and 16.1% showed radiographic abnormalities. Also 92.0% showed abnormal findings in EEGs at the time of diagnosis and 38.7% showed no change or an aggravation of the abnormalities.

We analyses risk factors by clinical characteristics (Table 1).

The recurrence rates according to sex were 22.2% for boys and 16.7% for girls. Sex was not significantly associated with recurrence (P=0.542).

The associations between the seizure recurrence and the age at seizure onset, age at which AEDs were first administered, age at which the seizures were controlled and age at AED discontinuation were analyzed. The mean ages at seizure onset, first administration of AEDs, control of seizures and AED discontinuation were 6.3±4.0, 7.3±3.9, 8.4±4.1, and 11.9±4.4 years of age, respectively. For these analyses, the patients were divided into subgroups according to age: infancy (1 month to 1 year of age), early childhood (1 to 5 years of age), late childhood (6 to 10 years of age), and adolescence (11 to 21 years of age).

The recurrence rates according to the age at first seizure were 29.4% for infancy, 17.4% for early childhood, 16.3% for late childhood, and 31.4% for adolescence. The differences in recurrence according to the age at first seizure were not significant (P=0.174).

The recurrence rates according to age at which AEDs were first administered were 25.9% for infancy, 19.2% for early childhood, 14.3% for late childhood, and 30.3% for adolescence. The recurrence rates were significantly higher when AEDs were first administered in infancy or adolescence than in early or late childhood (P=0.012).

The recurrence rates according to the age when seizure was controlled were 23.0% for infancy, 18.6% for early childhood, 13.6% for late childhood, and 29.7% for adolescence. The recurrence rates were significantly higher when seizures were controlled in infancy or adolescence than in early or late childhood (P=0.008).

While the recurrence rates according to the age at AED discontinuation were not available for patients in infancy, they were 22.4% for early childhood, 17.9% for late childhood, and 20.0% for adolescence. The age at AED discontinuation did not significantly affect rates of recurrence (P=0.870).

We identified 32 patients with family histories of epilepsy; the recurrence rate among these patients was 15.6%. The recurrence rate was 20.0% among patients without a family history of epilepsy. The difference between these rates was nonsignificant (P=0.421).

The recurrence rate was 17.3% among patients with histories of febrile convulsion and 20.8% among those with no history of febrile convulsion. There was no statistically significant difference between these recurrence rates (P=0.165). Among the 30 patients with histories of status epilepticus, the recurrence rate was 26.7%; while this rate was slightly higher than that among patients without histories of status epilepticus (19.2%), the difference was nonsignificant (P=0.245).

Among the 43 patients with histories of recurrence after previous discontinuation of AEDs, the recurrence rate was 48.8%. This rate was significantly higher than that among patients without histories of recurrence after previous discontinuation of AEDs (16.7%, P<0.001) (Fig. 1).

Seizure frequency didn’t be obtained from 50 patients. Except them, the recurrence rates of epilepsy were 19.1% among the patients with one seizure before treatment, 21.0% among those with two to nine seizures, and 12.5% among those with 10 or more seizures. The differences between these rates were nonsignificant (P=0.620).

The mean duration of AED administration was 4.5±2.3 years and when compared by dividing the duration of taking anticonvulsants by 3 years, the recurrence rate for those less than 3 years was 31.7% and for those over 3 years was 20.21%, which was nonsignificant (P=0.763). A single type of AED was used to control seizure for 324 patients—the majority; two types of AEDs were used in 87 cases, three types in 25 cases, and four or more types in five cases; the recurrence rates were 17.6%, 22.9%, 36.0%, and 20.0%, respectively. No statistically significant differences in these recurrence rates were found (P=0.395).

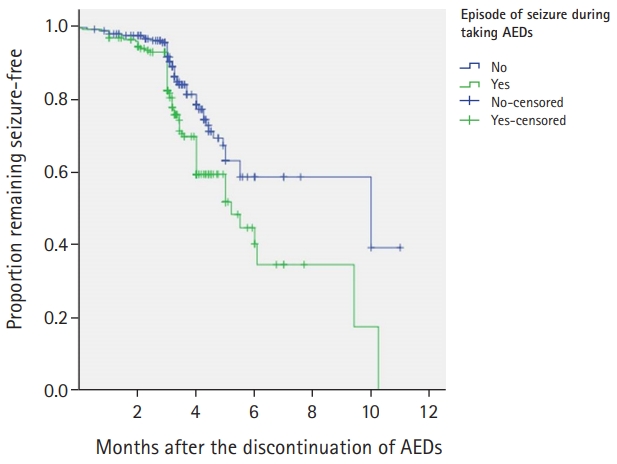

The recurrence rate was significantly lower among patients with no seizures during AED administration (12.0%) than among those who had episodes of seizure during AED administration (28.3%, P<0.001) (Fig. 2).

Neuroimaging was tested in patients except 56 patients who failed sedation treatment, rejected examinations, or were presumed to be epilepsy syndrome in EEG findings. Of the 385 patients who received brain computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations, abnormalities associated with epilepsy were found in 65 (Table 2), while none were found in 320. Their recurrence rates were 21.5% and 22.8%, respectively. The difference between these rates was not statistically significant (P=0.805).

EEGs obtained at the time of diagnosis were analyzed abnormalities were found in 409 patients, while none were found in 32; their recurrence rates were 19.6% and 21.9%, respectively. While the recurrence rate was higher among patients with normal EEG findings, the difference between the two rates was nonsignificant (P=0.505). Among the patients with EEG abnormalities, background EEG aberrations were found in 77 patients, focal epileptiform discharges were found in 261 and generalized epileptiform discharges were found in 71.

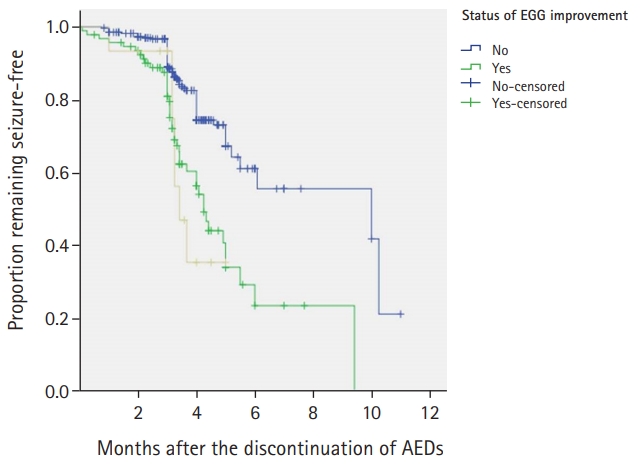

All patients underwent EEG examinations more than once before the discontinuation of AEDs, and the changes were compared with the initial finding. Among the 409 patients with abnormal EEGs at the time of diagnosis, 337 showed improvements, while 72 showed either no change or an aggravation of the abnormalities; their recurrence rates were 14.5% and 43.1%, respectively. The rate of recurrence was significantly higher among the patients whose EEG showed no change or an aggravation (P=0.039) (Fig. 3).

To assess neurological disability presented by the patients, we analyzed data obtained from neurological examination, language tests, and developmental tests. Neurological abnormalities ranging from developmental delay to mental retardation or cerebral palsy were identified in 112 patients. The recurrence rate among these patients was 25.9% and that among the patients without neurological disability was 17.6%. Though a trend was observed, the difference between these rates was nonsignificant (P=0.065).

Patients that could be classified as special epileptic syndrome were classified by EEG examination, and there were 48 benign rolandic seizures, 28 absent seizures, three Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, and six photosensitive epilepsy. The recurrence rate was 16.7% (8/48) in benign rolandic seizures, 21.4% (6/28) in absent seizures, 66.7% (2/3) in Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and 33.3% (2/6) in photosensitive epilepsy, but the difference between these rates was not statistically significant (P=0.085).

The present study observed the overall recurrence rate within 1 year after the discontinuation of AEDs to be 19.7% (87/441). When evaluated according to the timing of AED discontinuation, the highest rate of recurrence was observed during AED tapering 43.7% (38/87). We further identified the following factors as being significantly associated with recurrence of epilepsy: the age at which AEDs were first administered and seizures were controlled, a history of epilepsy recurrence after previous discontinuations of AEDs, an episode of seizure during AED administration, and no improvement in EEG findings across AED administration.

When timing the discontinuation of AEDs, medical factors as well as other individual factors should be considered [6]. The will of patients and their caregiver, their economic conditions, the adverse effects of drugs, and comorbidity can also affect the decision to discontinue AED administration. Numerous studies have sought to elucidate the factors associated with the recurrence of epilepsy after the discontinuation of AEDs to help inform this decision. For instance, upon reviewing the results from various studies, the American Academy of Neurology reported in 1996 that seizure-free period of 2 to 5 years, normal results from neurological examination, and the normalization of EEG during treatment lessened the risk of recurrence [7]. In addition, the risk of recurrence reportedly increases when the cause of epilepsy is symptomatic [8-10] and decreases when patients show an early response to the first administration of AED [8,11].

Regarding the differences in the risk of recurrence according to the age at seizure onset, several reports have found that the risk increases in adolescence; Shinnar et al. [12] defined this period as beginning at the age of 12, while Dooley et al. [13] and Chung et al. [14] considered adolescence to begin at the age of 10. Emerson et al. [15] reported that the recurrence rate is higher when the patient experiences his or her first seizure at the age of 2 years or younger. Although recurrence rates according to the age at seizure onset were higher in the infancy and adolescence relative to those in early and late childhood, the differences were not statistically significant in this study.

In some studies, there was no association between recurrence and histories of recurrence after previous discontinuations of AEDs and when epilepsy recurred after previous discontinuations of AED, the re-administration of AEDs lead to the remission of epilepsy [13,16]. However, in our study, the rate of recurrence was 48.8% among the patients with histories of epilepsy recurrence after previous discontinuations of AED, while a rate of 16.7% was observed among the patients without epilepsy recurrence after previous discontinuations of AED.

As for episodes of seizure during administering AEDs, Chung et al. [14] reported the recurrence of seizures during administering AEDs did not appear to be related to relapse. However, Specchio and Beghi [11] reported a connection as in this study.

This study performed an analysis of EEG results obtained at the time of diagnosis and before the discontinuation of AEDs. While Shinnar et al. [12] and Emerson et al. [15] reported that EEG abnormalities identified before discontinuations of AED treatment cannot predict the risk of recurrence, we found that there was a significantly higher recurrence rate among patients whose EEG results did not improve than among those whose results did (43.1%, 14.5%, respectively). Hence, our study observed that improvement in EEG findings (across treatment) is more predictive of recurrence than is the EEG obtained at the time of diagnosis.

Hippocampal atrophy or sclerosis identified with MRI is reportedly associated with a high rate of epileptic recurrence [2]. On the other hand, Lossius et al. [17] reported that abnormal findings from MRI are not predictive factors for epilepsy recurrence. Similarly, our study found the recurrence rate to be 21.5% in the presence of radiographic abnormalities and 22.8% in their absence, but it was not a significant predictor of epileptic recurrence. That’s because the abnormal MRI was considered as a case of simple ventriculomegaly as well as lesions with a high recurrence rate such as hippocampal sclerosis.

According to some studies [6,11,18], neurological disability increase the risk of epilepsy recurrence. While the present study found that the recurrence rate of epilepsy was higher among patients with neurological disability than among those without them (25.9%, 17.6%, respectively), this difference was nonsignificant.

As for the number of AEDs administered to control seizures, some studies [14,15] have reported an increase in the recurrence rate if multiple anticonvulsants were administered, but in other study [12], the risk of recurrence did not increase even if multiple AEDs were administered likes our study..

There are some limitations in our study. It is limited by its retrospective nature as well as by its use of data obtained from a single institute. It was further limited by only having monitored the patients’ treatment when the patients revisited our hospital through the outpatient clinic or emergency room. Prospective studies that perform more regular monitoring of the patients’ clinical progress and an accurate analysis of treatment compliance are warranted. As the follow-up period for pediatric patients tends to be limited—unlike that for adult patients—and such patients generally visit a different department when they become adults, collaboration with the Department of Neurology will be needed in the future to analyze the long-term recurrence rates of epilepsy. Moreover, differences in the diagnosis rate caused by the development of EEG and radiographic equipment during the 10 years of follow-up period, as well as differences in the treatment rate caused by changes in therapeutic agents, could have biased our study results.

Finally, there are a few epilepsy syndromes that have a high probability of recurrence so that AEDs discontinuation is not suggested. These include Lennox-Gastaut syndrome, Dravet syndrome or severe brain lesions such as brain cell migration disorder [19]. However, we attempted to taper AEDs in our study if there was a clear improvement in EEG or when the caregiver requested an end to treatment for their children whose epilepsy had been well-controlled for at least 2 years without the improvement of EEG.

However, compared to some studies that have analyzed the factors affecting the recurrence of epilepsy in Korea [2,20], our study included a relatively large number of pediatric patients and that is the strength of this study.

In conclusion, the risk of recurrence may be high if (1) the patient was an infant or an adolescent when AEDs were first administered or when the seizures were controlled; (2) no (or less) improvement in EEG finding during AED administration; (3) he/she experienced seizure during AED administration; or (4) he/she has a history of epilepsy recurrence after previous discontinuation of AEDs. Therefore, the discontinuation of AEDs should be considered with greater care for these patients especially during tapering period.

Notes

Author contribution

Conceptualization: SJK. Data curation: JHC and SJK. Formal analysis: JHC. Methodology: SJK. Project administration: SJK. Visualization: JHC. Writing-original draft: JHC. Writing-review & editing: SJK.

Fig. 1.

Differences in recurrence according to a history of seizure recurrence after previous discontinuation of antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) assessed through Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and the log-rank significance test.

Fig. 2.

Differences in recurrence according to the incidence of seizures during antiepileptic drug (AED) administration assessed through Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and the log-rank significance test.

Fig. 3.

Differences in recurrence according to improvements in electroencephalographic (EEG) findings assessed through Kaplan-Meier survival analysis and the log-rank significance test.

Table 1.

Risk factors for recurrence after the discontinuation of AEDs in children with epilepsy: univariate analysis

Table 2.

Abnormal findings of the radiologic work-up related to seizure recurrence

References

1. Collaborative Group for the Study of Epilepsy. Prognosis of epilepsy in newly referred patients: a multicenter prospective study of the effects of monotherapy on the long-term course of epilepsy. Epilepsia 1992;33:45-51.

2. Kim HB, You SJ, Ko TS. Outcome after discontinuation of antiepileptic drugs in well controlled epileptic children: recurrence and related risk factors. Korean J Pediatr 2004;47:66-75.

3. St Louis EK. Minimizing AED adverse effects: improving quality of life in the interictal state in epilepsy care. Curr Neuropharmacol 2009;7:106-14.

4. Peters AC, Brouwer OF, Geerts AT, Arts WF, Stroink H, van Donselaar CA. Randomized prospective study of early discontinuation of antiepileptic drugs in children with epilepsy. Neurology 1998;50:724-30.

5. Strozzi I, Nolan SJ, Sperling MR, Wingerchuk DM, Sirven J. Early versus late antiepileptic drug withdrawal for people with epilepsy in remission. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015;2015:CD001902.

7. Practice parameter: a guideline for discontinuing antiepileptic drugs in seizure-free patients. Summary statement. Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology 1996;47:600-2.

8. Berg AT, Shinnar S. Relapse following discontinuation of antiepileptic drugs: a meta-analysis. Neurology 1994;44:601-8.

9. Sillanpaa M, Schmidt D. Prognosis of seizure recurrence after stopping antiepileptic drugs in seizure-free patients: a long-term population-based study of childhood-onset epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2006;8:713-9.

10. Ramos-Lizana J, Aguirre-Rodriguez J, Aguilera-Lopez P, Cassinello-Garcia E. Recurrence risk after withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs in children with epilepsy: a prospective study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2010;14:116-24.

11. Specchio LM, Beghi E. Should antiepileptic drugs be withdrawn in seizure-free patients? CNS Drugs 2004;18:201-12.

12. Shinnar S, Berg AT, Moshe SL, Kang H, O'Dell C, Alemany M, et al. Discontinuing antiepileptic drugs in children with epilepsy: a prospective study. Ann Neurol 1994;35:534-45.

13. Dooley J, Gordon K, Camfield P, Camfield C, Smith E. Discontinuation of anticonvulsant therapy in children free of seizures for 1 year: a prospective study. Neurology 1996;46:969-74.

14. Chung SJ, Chung HJ, Choi YM, Cho EH. A follow-up study after discontinuation of antiepileptic drug therapy in children with well-controlled epilepsy: the factors that influence recurrence. Korean J Pediatr 2002;45:1559-70.

15. Emerson R, D'Souza BJ, Vining EP, Holden KR, Mellits ED, Freeman JM. Stopping medication in children with epilepsy: predictors of outcome. N Engl J Med 1981;304:1125-9.

16. Gebremariam A, Mengesha W, Enqusilassie F. Discontinuing anti-epileptic medication(s) in epileptic children: 18 versus 24 months. Ann Trop Paediatr 1999;19:93-9.

17. Lossius MI, Hessen E, Mowinckel P, Stavem K, Erikssen J, Gulbrandsen P, et al. Consequences of antiepileptic drug withdrawal: a randomized, double-blind study (Akershus Study). Epilepsia 2008;49:455-63.

18. Thurston JH, Thurston DL, Hixon BB, Keller AJ. Prognosis in childhood epilepsy: additional follow-up of 148 children 15 to 23 years after withdrawal of anticonvulsant therapy. N Engl J Med 1982;306:831-6.