|

|

- Search

| Ann Child Neurol > Volume 27(4); 2019 > Article |

|

Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to evaluate the efficacy and tolerability of everolimus, an oral mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor, for the treatment of tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) manifestations.

Methods

A retrospective analysis was conducted using an in-house research database with the keywords “tuberous sclerosis AND everolimus.” Twenty patients were treated with everolimus for TSC from 2013 to February 2019.

Results

The mean age of the 20 patients was 25.6 years (range, 0 to 57), and the average duration of everolimus treatment was 87.6 weeks (range, 0 to 290). Everolimus was given with a usual daily dosage of 5 to 10 mg (mean, 7.1) or 0.0625 to 0.5 mg for neonates. Twelve patients were prescribed everolimus for more than 1 year for kidney angiomyolipoma (AML). Two of those patients (16.7%) experienced reductions of >50% in tumor size, and four patients (33.3%) experienced reductions of 25% to 50%. The four patients who were prescribed everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) had 25% to 50% reductions. Neonates with cardiac rhabdomyoma showed significant tumor reduction with everolimus, but their tumors exhibited rebound size increases after treatment was halted. Of the three patients with intractable seizures, one patient became seizure-free, and two patients had >50% reductions. Overall, everolimus therapy was well tolerated.

Tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) is a disease in which hamartomas grow in the kidney, brain, heart, liver, and skin, resulting from the decreased or absent expression of the TSC1 (hamartin) or TSC2 (tuberin) genes [1,2]. The hamartin-tuberin complex serves to inhibit mechanistic target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1), and the loss of the complex activates mTORC1, leading to aberrant signals and tumor growth [3]. Rapamycin (sirolimus), a macrolide derived from Streptomyces hygroscopicus, and its analog molecules, including everolimus, are inhibitors of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) [4]. These drugs combine with a cytosolic protein, FK506-binding protein 12 (FKBP-12), across the cell membrane to form an FKBP-12-rapalog complex, which inhibits the ability of mTORC1 to interfere with proliferation and cellular metabolism of protein synthesis, neoangiogenesis, glycolysis, and proliferation [4]. Long-term use of these drugs also inhibits mTORC2, which affects both T and B cells, resulting in immunosuppression and glucose intolerance [4,5]. Everolimus is more specific to mTORC1 than sirolimus, and therefore, causes fewer metabolic side effects [5].

In 1999, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and the European Medical Agency (EMA) approved sirolimus to prevent rejection of kidney transplants in children aged 13 or older. The EXIST-I and II studies (examining everolimus in a study of TSC) showed that everolimus elicited a response rate superior to placebo for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA), renal angiomyolipoma (AML), and skin lesions in patients with TSC [6,7]. The interim analysis of the subsequent open-label extension phase also showed the stability of everolimus effects over time [8-10]. The U.S. FDA currently approves everolimus for adult patients with renal AML that does not require immediate surgery and patients aged 3 years or older with SEGA requiring therapeutic intervention who are not candidates for curative surgical resection. Furthermore, the EMA approved everolimus for add-on treatment in patients aged 2 years or older with seizures associated with TSC that have not responded to other treatments.

In Korea, there are several case reports about the use of everolimus targeted to renal AML or SEGA, but no large clinical study about efficacy and tolerability has been conducted to date. The aim of this study is to describe our center’s experience with everolimus in the management of multiple manifestations of TSC.

Using the Asan Medical Center’s in-house research database (ABLE) with the keywords “tuberous sclerosis AND everolimus,” all TSC patients who were treated with everolimus in Asan Medical Center were retrieved. Twenty patients received everolimus for TSC manifestations from 2013 to February 2019. A diagnosis of TSC was made according to the 2012 International TSC Consensus Conference [11]. Everolimus was prescribed according to the Korean FDA approval. However, one patient was enrolled in the EXIST-III study that evaluated everolimus for intractable seizures, and four neonates were treated with off-label use for cardiac rhabdomyoma (RHM) that caused cardiac outflow obstruction or cardiac arrhythmias. These patients were included in the patient cohort of this study.

The standard initial dose of everolimus was 4.5 mg/m2 administered as a single dose. In children and adolescents, everolimus was administered as 2.5, 5, or 7.5 mg once daily in patients with body surface areas of 0.5 to 1.2, 1.3 to 2.1, and >2.2 m2, respectively. For adults, 10 mg of everolimus once daily was prescribed for the initial dose. The dose was titrated in 2.5 mg increments or decrements to reach the trough level of 5 to 15 ng/mL. In neonates, the initial dose of everolimus was 0.0625 to 0.25 mg depending on body surface area, and the dose was titrated using the trough level weekly. The neonatal dose was estimated to be 0.65 mg/m2/day based on previous studies [12].

The effects of everolimus were evaluated by routine check-ups and imaging studies for the kidney, brain, and heart, which were performed every 3 to 12 months. To monitor the side effects of everolimus, complete blood counts, liver and kidney function tests, serum triglycerides, cholesterol, and drug trough levels were measured.

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Asan Medical Center (IRB 2019-1292). Written informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study but was obtained from each of the neonatal parents.

Twenty patients were treated with everolimus in TSC during the trial period. Table 1 summarizes the clinical and genetic data for enrolled patients. Thirteen patients were male, and their median age at initiation of treatment was 25.6 years (range, 0 to 57.2). The median period of everolimus treatment was 87.6 weeks (range, 0.4 to 289.6). Genetic analysis was carried out in 12 of the 20 cases, and seven patients had a mutation in TSC2, and no patients had a TSC1 mutation.

Fifteen of twenty patients (75.0%) had renal AMLs. Neuroimaging revealed tubers in 11/20 patients (55.0%), subependymal nodules (SENs) in 12 (60.0%), and SEGA in seven patients (35.0%). Overall, 10/20 patients (50.0%) experienced epileptic seizures, and among these, three patients presented with intractable epilepsy. Cardiac RHM were present in six patients. Retinal hamartomas were present in three individuals. Dermatologic manifestations, including facial angiofibroma, were found in 14 patients.

Adolescents and adults received everolimus in doses ranging from 5 to 10 mg daily (mean, 7.1), while newborns up to 3 months received everolimus in doses ranging from 0.0625 to 0.5 mg daily. Treatment was ongoing in 12 of 20 patients at the time of this writing, and three patients discontinued everolimus after successful reduction of renal AML or cardiac RHM. Early withdrawal of everolimus was observed in five patients including four patients with side effects, and one patient died from disease progression during the treatment.

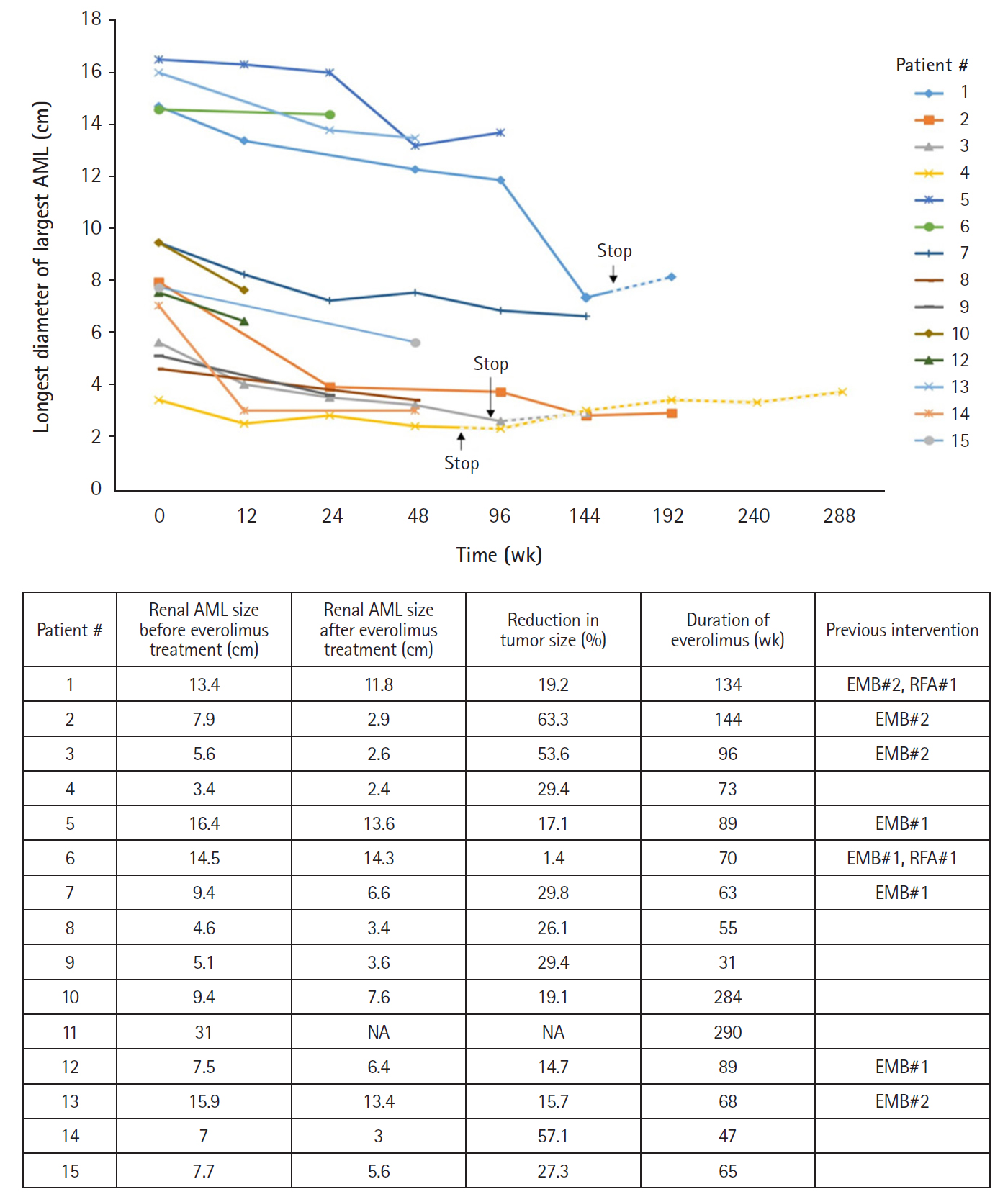

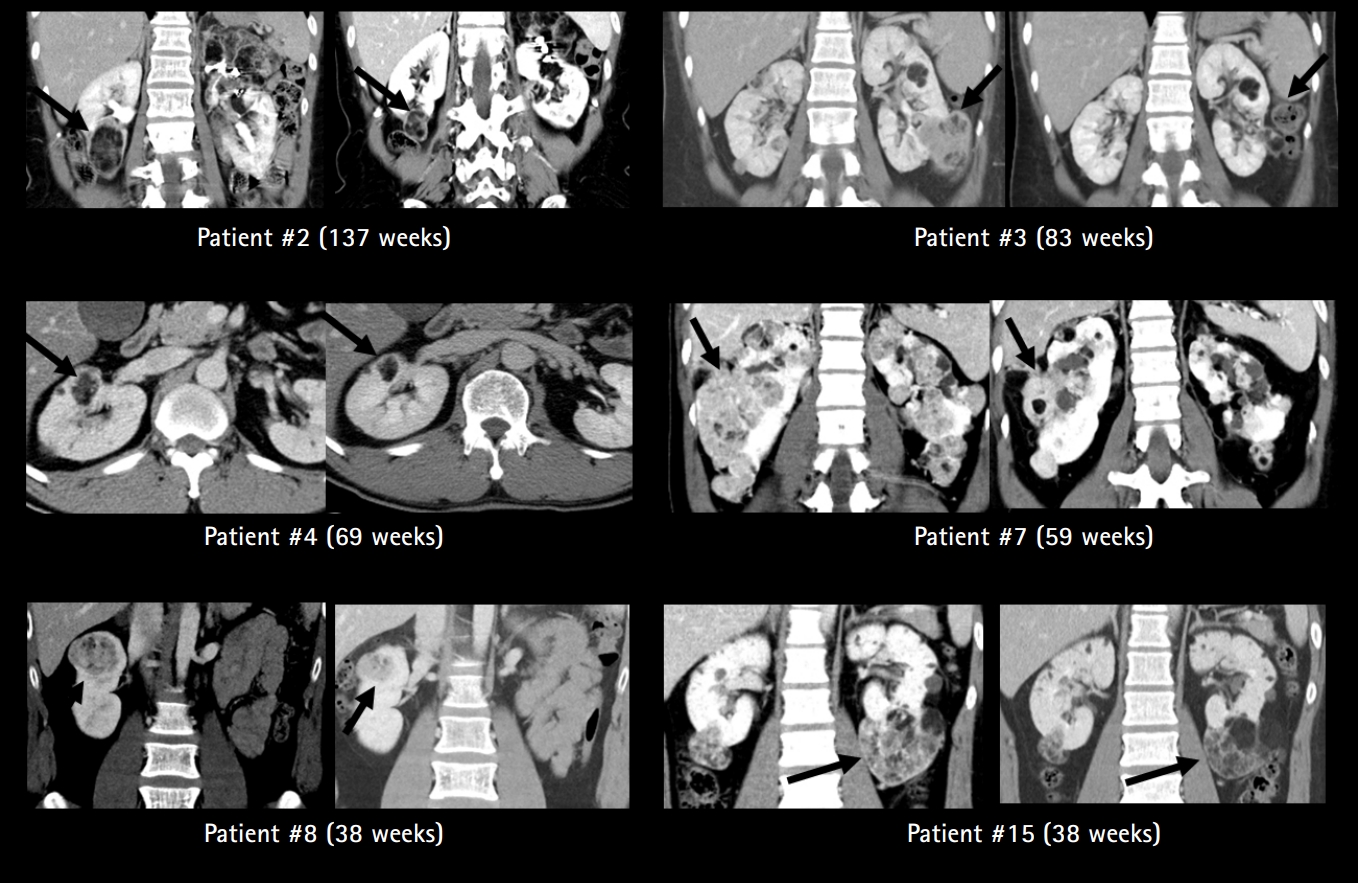

Fifteen patients were diagnosed with renal AML, all of which were bilateral and multifocal. Eight patients had received interventional therapy including selective angioembolization prior to everolimus therapy and 12 had received everolimus for more than 1 year. Before treatment, the mean longest diameter of largest AML was 9.2±4.4 cm (range, 3.4 to 16.4). After a mean of 106 weeks of drug administration, all of the AML nodules reduced in size, with the largest mass decreasing to 6.9±4.5 cm (range, 2.4 to 14.3) (Fig. 2). In two patients (16.7%) the size of the AML decreased by >50%, four (33.3%) experienced decreases of 25% to 50%, five (41.7%) experienced decreases of 10% to 25%, and none had progression of tumors (Fig. 3).

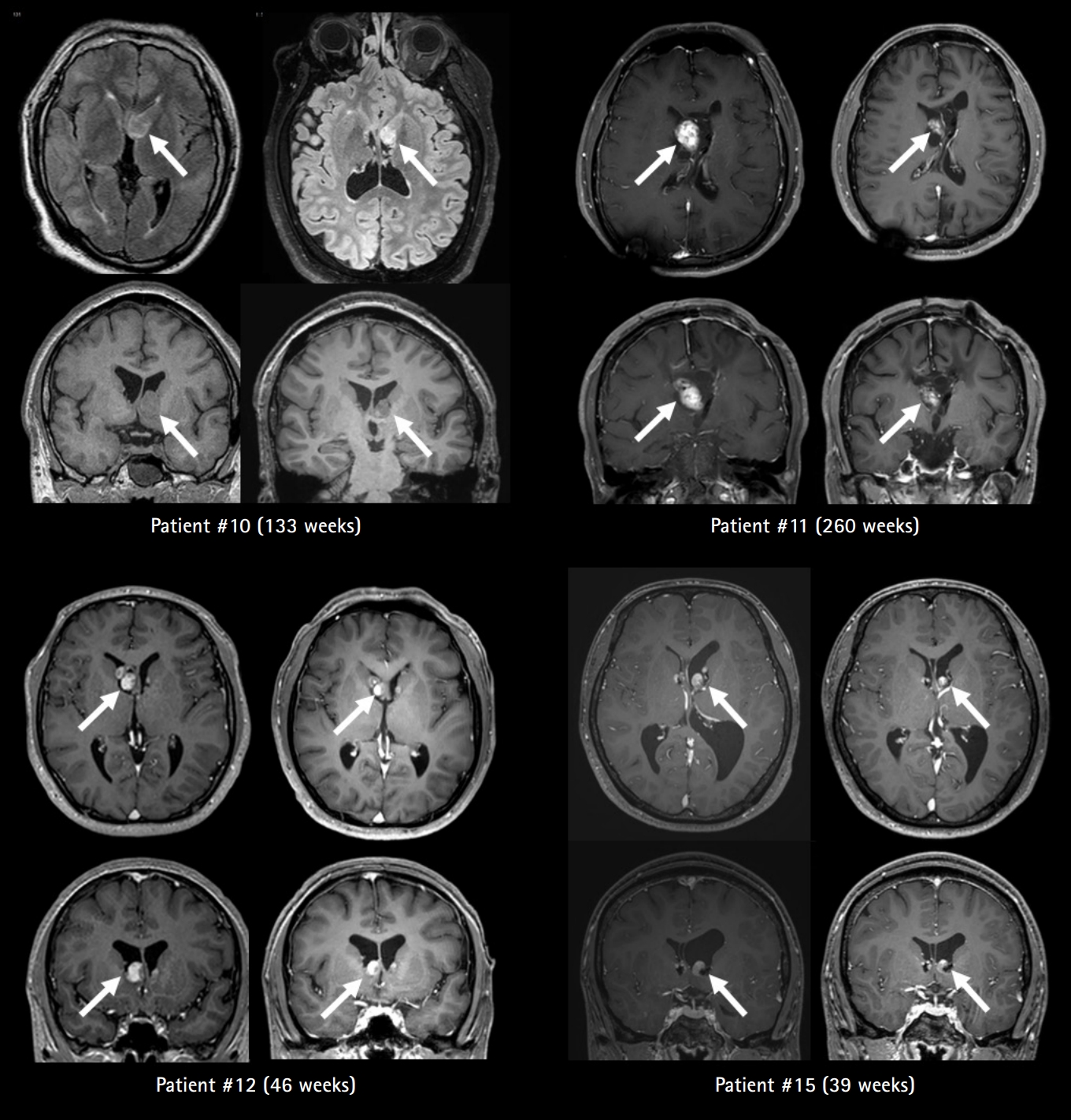

Seven of twenty patients (35.0%) developed SEGA during the observation period. Four of seven patients with SEGA had previous surgical treatment. With the exception of two patients (Patients #14 and #16) who had no follow-up data, the largest size of SEGA before drug use was 19.2±8.9 mm (range, 10 to 33) and decreased to 12.6±4.5 mm (range, 7 to 18) after everolimus treatment for a mean duration of 106 weeks (Fig. 4).

Four of seven patients were treated with everolimus due to growing or symptomatic SEGA. These four patients experienced a 25% to 50% size reduction. A significant reduction of SEGA size was documented by magnetic resonance imaging after a short follow-up of 2 and 3 months of treatment, respectively (Fig. 5).

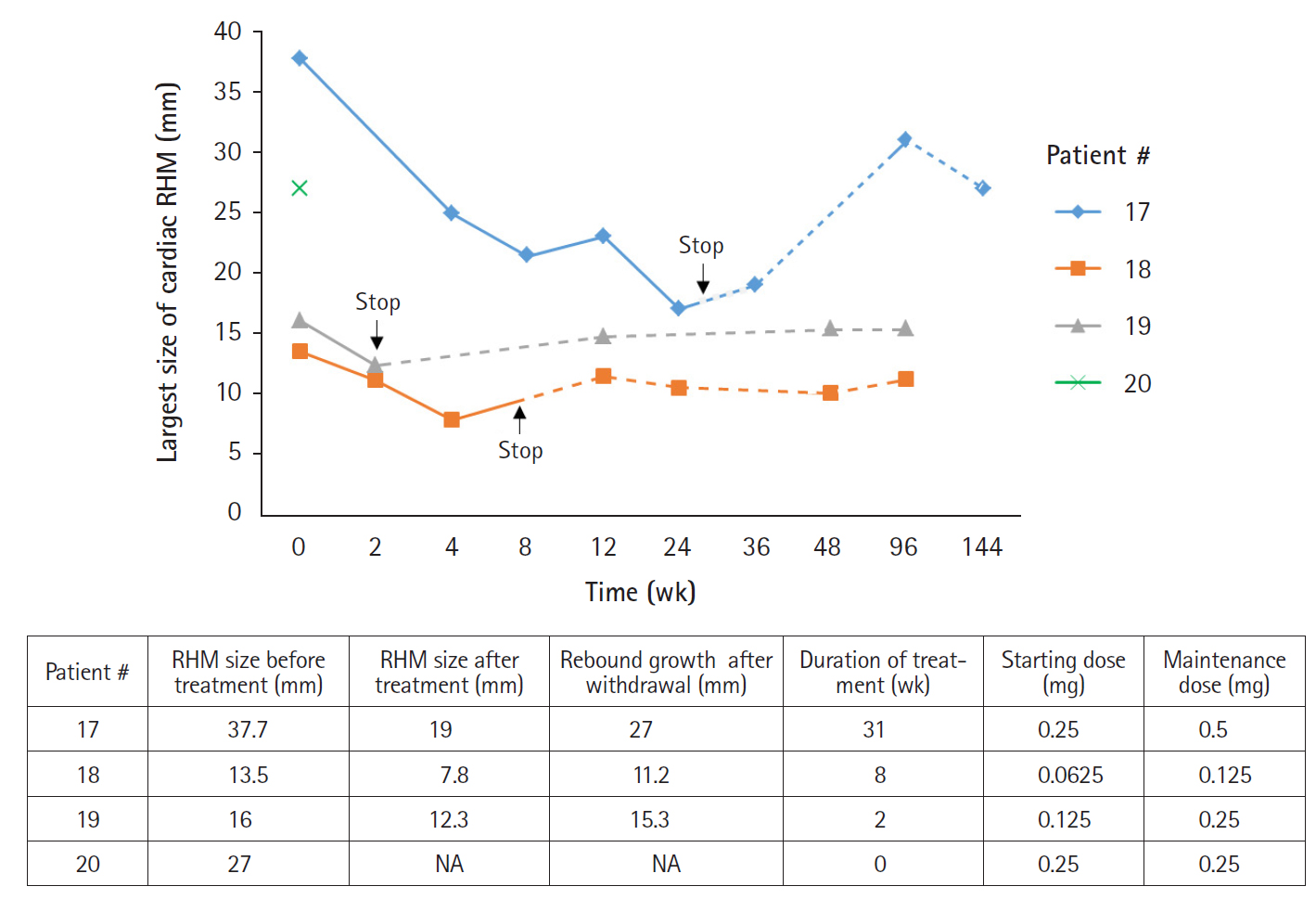

Six of twenty patients (30.0%) showed cardiac RHM at birth. In four of these six cases, everolimus was initiated due to obstruction of cardiac outflow or fatal cardiac arrhythmias refractory to treatment with atenolol or isoproterenol in neonatal periods. The patients received 0.0625 to 0.25 mg of everolimus as a starting dose and were titrated to reach the trough level of 5 to 15 ng/mL.

One patient (Patient #20) died due to a RHM-induced right ventricle obstruction within 20 days of birth and treatment with everolimus. In the remaining three cases, initiation of everolimus therapy led to a rapid decrease of associated RHM size and control of cardiac arrhythmias. Discontinuation of everolimus caused regrowth of the cardiac RHM (Fig. 6).

Epilepsy was diagnosed for 10/20 patients (50.0%). Each of these 10 of these patients had cortical tubers, SEN, or SEGA. Three patients had treatment-resistant epilepsy at the start of everolimus treatment, and one patient (Patient #16) who was included in the EXIST-III study became almost seizure-free on a combination therapy consisting of everolimus, lamotrigine, topiramate, and clobazam. Two patients (Patients #12 and #15) who had previously experienced focal seizures that were refractory to two to three antiepileptic drugs, experienced a 50% reduction in seizure frequency with everolimus treatment. However, Patient #16 experienced seizure recurrence after discontinuation of everolimus due to an adverse event (emotional instability).

Skin lesions (facial angiofibroma) associated with tuberous sclerosis were present at baseline in 14 patients. Nine of 14 patients (64.3%) showed markedly decreased skin lesions after everolimus administration.

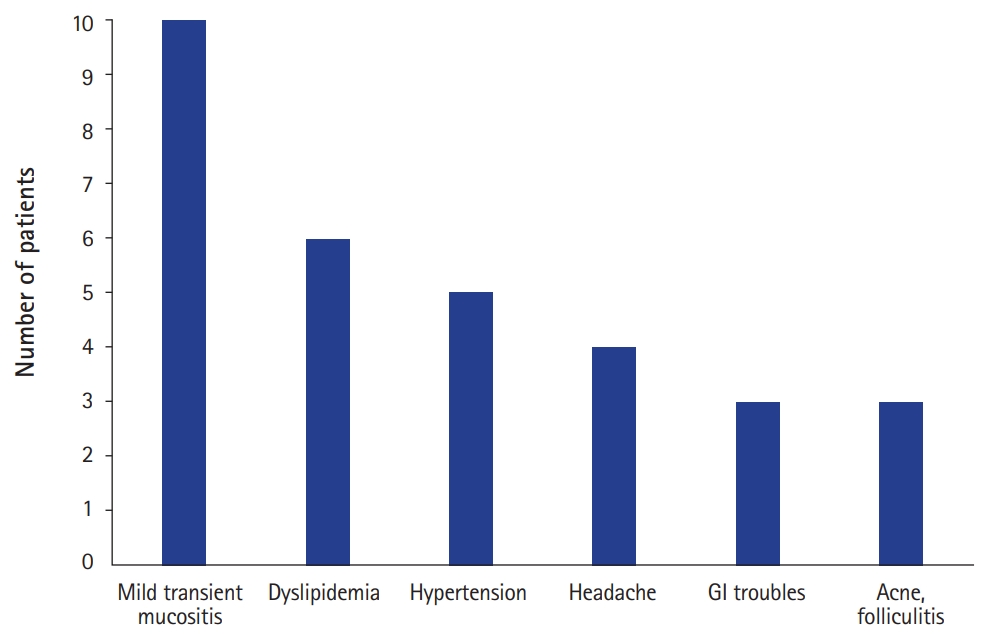

Adverse events occurred in 17 cases (85.0%) with a median of 3.2 adverse events (range, 0 to 11) per individual, including mild transient mucositis (10 patients); increased serum cholesterol and triglycerides (six patients); hypertension (five patients); headache (four patients); gastrointestinal troubles such as nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea (three patients); and worsening of acne or folliculitis (three patients). Severe adverse events resulting in discontinuation or dose modification were reported in five patients, including drug-induced interstitial lung disease, persistent fever, neutropenia, emotional instability, and severe oral ulcer (Fig. 7).

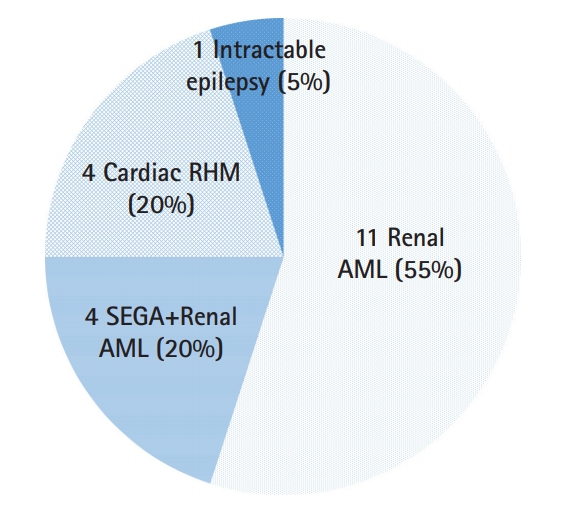

We collected data from 20 TSC patients from a single tertiary center in Korea. Treatment was initiated for renal AMLs (15/20, 75.0%), renal AML and SEGA (4/20, 20.0%), cardiac RHM (4/20, 20.0%), and intractable epilepsy (1/20, 5.0%). Therapeutic benefits following everolimus treatment were observed as decreases in renal AML, SEGA, and cardiac RHM size, and reductions in arrhythmia or seizure frequency, or improvements in skin lesions. Everolimus therapy was well tolerated. Treatment is currently ongoing in 12/20 patients (60.0%), and another three patients are stable with reduced tumor burden (renal AML in one case; cardiac RHM in two cases) even after discontinuing everolimus treatment. To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest cohort study with TSC-related multiple manifestations that were successfully treated with everolimus in Korea. Although everolimus was initiated for a single manifestation of a small number of patients, most patients had various manifestations in multiple organs, and we eventually confirmed the integrated efficacy of everolimus treatment on multiple manifestations.

TSC patients showed a wide variety of organ system involvement and severity. TSC-related tumors typically develop in later life, but cardiac RHM is often diagnosed in early life or even prenatally [13]. Because clinical manifestations associated with TSC can be life-threatening, proper monitoring and management are needed to reduce disease-related complications and mortality. Recently published long-term data from EXIST-I and EXIST-II have shown a pronounced and sustained clinical benefit of everolimus [8,10]. It was also confirmed that the number of patients with tumor regression increased over time. The proportion of patients with size reductions of >50% increased from 45% in 2 years to 62% in 4 years [6,9] in renal AMLs, and the SEGA response rate increased to 58% (95% confidence interval, 47.9 to 67.0) with a median duration of 47.1 months of everolimus treatment [10]. In our study, except for four neonates, 16 adolescent and adult patients (mean age, 32.0 years) were treated with everolimus for mean of 106.9 weeks (range, 30.7 to 289.6) with mean dose intensity of 8.8 mg/day. Tumor regression of >50% was observed in only 3/14 (21.4%) patients with renal AMLs and no patients with SEGA. Most patients experienced a 25% to 50% reduction in tumor size. The mean longest diameter of largest AML decreased by 28.8%, and SEGA size decreased by 31.3% on average, which is less responsive than those reported in previous studies [9,10]. This difference in response rate may have resulted from a difference in measurement; this study used the longest diameter rather than the volume of tumors, the patient cohort was small, and the study period was short. In addition, it appears necessary to observe the response rate to everolimus over a long period.

Although it is generally known to exhibit good outcomes and tumor regression, cardiac RHM can be fatal, and immediate intervention may be required in neonatal or young children [14,15]. The U.S. FDA has not approved everolimus for cardiac RHM, yet several studies have observed clinical benefit and safety in using everolimus for the treatment of cardiac RHM in infants and preschool children [12,16,17]. In neonates, even with a small dose for short term (15 days to 13 months), there is a significant size reduction of cardiac RHM, and everolimus therapy has been well tolerated [16]. In the current study, four neonates with cardiac RHM that had induced obstruction of cardiac outflow or uncontrolled cardiac arrhythmia were treated with everolimus, and they experienced successful tumor reduction. However, one patient (Patient #18) presented neutropenia as a severe adverse effect of everolimus. Therefore, even with the strong potential of spontaneous regression of cardiac RHM, everolimus should be considered as a therapeutic option for patients at risk of serious cardiac events, including heart failure, outflow obstruction, and arrhythmias.

TSC-related tumors shrink and stabilize with mTOR inhibitor treatment, but after treatment is stopped, tumor volume tends to increase again [18,19]. For this reason, it is often difficult to determine how long a patient should be maintained on a maintenance dose of everolimus to treat TSC-related tumors. In our cohort, three out of 12 patients who were treated with everolimus for more than 1 year for renal AMLs discontinued treatment, and all of them experienced rebound tumor volume increases. Renal AML increased from 7.3 to 8.1 cm (111.0%) over 45 weeks in Patient #1, from 2.6 to 2.9 cm (111.5%) over 54 weeks in Patient #3, and from 2.3 to 3.7 cm (160.9%) over 182 weeks in Patient #4. However, the size of these rebound tumors was the same or smaller than size of the tumor before everolimus treatment was initiated. In cardiac RHM, rebound growth of tumors was also observed in the three patients (Patients #17, #18, and #19) who discontinued everolimus treatment due to a reduction in tumor size, but the tumors of these patients did not exceed the original size and did not cause hemodynamic instability or arrhythmia. This is consistent with previous studies in which renal AML or cardiac RHM rebound growth occurred following withdrawal of mTOR inhibitors [12,19,20]. The regrowth of tumors after the cessation of an mTOR inhibitor suggests that continued treatment with everolimus in TSC patients may be required to sustain significant tumor volume reduction. Alternatively, if problems emerge during treatment, such as severe adverse effects, short-term mTOR inhibitor use during the critical period followed by tumor monitoring can be performed. Therefore, it is necessary to study the proper timing of dose reduction or discontinuation while administering mTOR inhibitors in TSC patients.

Because TSC is a lifelong disease that begins at a very early age, it is important to consider the long-term effects of mTOR inhibitors on overall safety and growth in young children [21]. A cohort analysis of mTOR inhibitor treatment in children who received renal transplants reported that approximately 5 years of mTOR treatment had no significant impact on growth and pubertal development [22]. However, large-scale studies of the long-term effects and safety of mTOR inhibitor administration in patients with TSC over 10 or 20 years is still required.

In this study, adverse events were reported in 17 cases (85.0%) in the order of mucositis, dyslipidemia, hypertension, headache, gastrointestinal troubles, and worsening of acne or folliculitis. In order to prevent oral mucositis, patients were instructed to swallow the drug as soon as possible, and edible-wrapping papers was recommended to use. Serious adverse events including drug-induced interstitial lung disease, persistent fever, neutropenia, emotional instability, and severe oral ulcer resulted in discontinuation or dose modification in five patients. However, these events were reversible, returning to normal when the drug was reduced or dropped.

In this retrospective study, despite the small patient cohort, the data show a significant treatment response to everolimus in patients with TSC-associated epilepsy and cardiac RHM in addition to renal AML and SEGA. Further long-term studies with larger patient cohorts will be required to confirm the effectiveness, safety, timing, and duration of everolimus treatment in TSC patients.

In conclusion, everolimus, an mTOR inhibitor, can be effective for multiple clinical manifestations of TSC patients. However, clinicians should also be aware of the adverse events profile of everolimus and continue to study the long-term efficacy and frequency of side effects in the future.

Notes

Author contributions

Conceptualization: HA, MSY, and TSK. Data curation: HA, MSY, and HNJ. Formal analysis: HA and MSY. Methodology: HA and MSY. Project administration: HA and MSY. Visualization: HA and MSY. Writing-original draft: HA. Writing-review & editing: MSY, CS, and TSK.

Acknowledgments

This work was presented at the symposium of the Korean Child Neurology Society (2019 May).

Fig. 1.

Reasons for the initiation of treatment with everolimus, an mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor. AML, angiomyolipoma; RHM, rhabdomyoma; SEGA, subependymal giant cell astrocytoma.

Fig. 2.

Tuberous sclerosis complex-related renal angiomyolipima (AML) size changes under everolimus treatment. Fifteen patients were diagnosed with renal AML, and 8 of them had previous AML therapy, including percutaneous embolization (EMB) or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) due to ruptured AML or large mass size. The data for Patient #11 were not included due to the absence of follow-up imaging. The mean longest diameter of the largest AML was 9.2±4.4 cm (range, 3.4 to 16.4). After everolimus treatment for a mean duration of 106 weeks, the size of renal AML decreased to 6.9±4.5 cm (range, 2.4 to 14.3). NA, not available.

Fig. 3.

Contrast-enhanced coronal computed tomographic images illustrating renal angiomyolipomas (AML) of patients who had been treated with everolimus for more than 1 year and showed size reductions of more than 25%. The left image in each pair of patient images shows bilateral multiple renal AML before initiation of everolimus treatment. Arrows indicate the largest AML in each patient. The right image in each pair of patient images shows the decreased size of renal AML in each patient after oral everolimus treatment for the number of weeks indicated. Patients #2 and 3 experienced more than 50% size reductions, and Patients #4, 7, 8, and 15 experienced 25% to 50% size reductions on the follow-up. The remaining five patients (Patients #1, 5, 10, 12, and 13) had 10% to 25% size reductions, and none had progression of tumors.

Fig. 4.

Tuberous sclerosis complex-related subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA) size change under everolimus treatment. Data of Patients #14 and 16 were not included due to the absence of follow-up imaging. The largest size of SEGA before treatment was 19.2±8.9 mm (range, 10 to 33) and decreased to 12.6±4.5 mm (range, 7 to 18) after everolimus treatment for a mean duration of 106 weeks. NA, not available.

Fig. 5.

Axial and coronal T2-weighted and T1-weighted with or without gadolinium MRI sections of four patients (Patients #10, 11, 12, and 15) treated with everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytoma (SEGA). All patients were treated with everolimus due to growing or symptomatic SEGA (left image in each pair of patient images). All patients on follow-up after the indicated number of weeks exhibited marked reduction of SEGA volume (right image in each pair of patient images). All patients experienced a 25% to 50% size reduction after a mean treatment duration of 119 weeks. Arrows indicate the largest SEGA in each patient.

Fig. 6.

Four patients who were treated with everolimus due to cardiac rhabdomyoma (RHM) induced obstruction of cardiac outflow or cardiac arrhythmias in neonatal periods. Patient #20 died 3 days after birth and initiation of everolimus due to a rhabdomyoma-induced right ventricle obstruction. In the remaining three patients, initiation of everolimus therapy led to a decrease in rhabdomyoma size and therapeutic control of cardiac arrhythmias. Discontinuation of treatment in the presence of stable disease caused regrowth of the cardiac rhabdomyoma. NA, not available.

Fig. 7.

Safety profile of oral everolimus. Adverse events developed in 17/20 (85.0%) patients with a median of 3.2 adverse events (range, 0 to 11) per individual. Severe adverse events resulting in discontinuation or dose modification were reported in five patients including drug-induced interstitial lung disease (Patient #1), persistent fever (Patient #3), neutropenia (Patient #17), emotional instability (Patient #16), and oral ulcer (Patient #9). GI, gastrointestinal.

Table 1.

Clinical data of mammalian target of rapamycin inhibitor therapy on TSC-related manifestations

References

2. Franz DN, Bissler JJ, McCormack FX. Tuberous sclerosis complex: neurological, renal and pulmonary manifestations. Neuropediatrics 2010;41:199-208.

3. Huang J, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex: a molecular switchboard controlling cell growth. Biochem J 2008;412:179-90.

5. Tenderich G, Fuchs U, Zittermann A, Muckelbauer R, Berthold HK, Koerfer R. Comparison of sirolimus and everolimus in their effects on blood lipid profiles and haematological parameters in heart transplant recipients. Clin Transplant 2007;21:536-43.

6. Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, Zonnenberg BA, Frost M, Belousova E, et al. Everolimus for angiomyolipoma associated with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis (EXIST-2): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:817-24.

7. Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, Bebin EM, Frost M, Kuperman R, et al. Efficacy and safety of everolimus for subependymal giant cell astrocytomas associated with tuberous sclerosis complex (EXIST-1): a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet 2013;381:125-32.

8. Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, Zonnenberg BA, Frost M, Belousova E, et al. Everolimus for renal angiomyolipoma in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis: extension of a randomized controlled trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2016;31:111-9.

9. Bissler JJ, Kingswood JC, Radzikowska E, Zonnenberg BA, Belousova E, Frost MD, et al. Everolimus long-term use in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: four-year update of the EXIST-2 study. PLoS One 2017;12:e0180939.

10. Franz DN, Belousova E, Sparagana S, Bebin EM, Frost MD, Kuperman R, et al. Long-term use of everolimus in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex: final results from the EXIST-1 study. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158476.

11. Northrup H, Krueger DA; International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Group. Tuberous sclerosis complex diagnostic criteria update: recommendations of the 2012 International Tuberous Sclerosis Complex Consensus Conference. Pediatr Neurol 2013;49:243-54.

12. Goyer I, Dahdah N, Major P. Use of mTOR inhibitor everolimus in three neonates for treatment of tumors associated with tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatr Neurol 2015;52:450-3.

13. Jozwiak S, Schwartz RA, Janniger CK, Bielicka-Cymerman J. Usefulness of diagnostic criteria of tuberous sclerosis complex in pediatric patients. J Child Neurol 2000;15:652-9.

14. Hinton RB, Prakash A, Romp RL, Krueger DA, Knilans TK; International Tuberous Sclerosis Consensus Group. Cardiovascular manifestations of tuberous sclerosis complex and summary of the revised diagnostic criteria and surveillance and management recommendations from the International Tuberous Sclerosis Consensus Group. J Am Heart Assoc 2014;3:e001493.

16. Dahdah N. Everolimus for the treatment of tuberous sclerosis complex-related cardiac rhabdomyomas in pediatric patients. J Pediatr 2017;190:21-6.

17. Saffari A, Brosse I, Wiemer-Kruel A, Wilken B, Kreuzaler P, Hahn A, et al. Safety and efficacy of mTOR inhibitor treatment in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex under 2 years of age: a multicenter retrospective study. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2019;14:96.

18. Bissler JJ, McCormack FX, Young LR, Elwing JM, Chuck G, Leonard JM, et al. Sirolimus for angiomyolipoma in tuberous sclerosis complex or lymphangioleiomyomatosis. N Engl J Med 2008;358:140-51.

19. Bissler JJ, Nonomura N, Budde K, Zonnenberg BA, Fischereder M, Voi M, et al. Angiomyolipoma rebound tumor growth after discontinuation of everolimus in patients with tuberous sclerosis complex or sporadic lymphangioleiomyomatosis. PLoS One 2018;13:e0201005.

20. Mlczoch E, Hanslik A, Luckner D, Kitzmuller E, Prayer D, Michel-Behnke I. Prenatal diagnosis of giant cardiac rhabdomyoma in tuberous sclerosis complex: a new therapeutic option with everolimus. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 2015;45:618-21.